Volume 12, Issue 2 (9-2026)

J Sport Biomech 2026, 12(2): 320-336 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Soltani M, Fatahi A, Heidari F. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Achilles Tendon Biomechanics in Healthy Male Wistar Rats. J Sport Biomech 2026; 12 (2) :320-336

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-479-en.html

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-479-en.html

1- Department of Sports Biomechanics, CT.C, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran.

2- Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1826 kb]

(14 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (26 Views)

Full-Text: (9 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

Dietary supplements—defined as nutrients or bioactive compounds used to enhance health or performance beyond what is typically achieved through a standard diet—are widely consumed by both athletes and the general population (1–3). Athletes commonly use supplements not only for direct performance enhancement but also for indirect benefits such as supporting training adaptations, optimizing body composition, facilitating injury recovery, and improving mood and well-being. Over the past two decades, supplement use has increased substantially and now includes a broad range of products, including carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, minerals, herbs, and plant-derived extracts (1,4–12). Vitamin D, a secosteroid prohormone and precursor of the active metabolite calcitriol, plays a central role in calcium–phosphate homeostasis, bone metabolism, skeletal muscle function, and the modulation of inflammatory responses. It has been shown to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), while upregulating the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10). In addition, vitamin D promotes cytoprotective effects in tenocytes through activation of ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, mechanisms that may contribute to tendon repair and tissue homeostasis (13–18). Previous evidence suggests that vitamin D supplementation may enhance tendon strength, stimulate collagen synthesis, and support extracellular matrix integrity, particularly in populations exposed to high mechanical loads, such as athletes, or in aging individuals, potentially accelerating recovery following tendon injury (19–22).

The biomechanical properties of tendons—including maximum force (Fmax), stiffness, deformation, and absorbed energy—are key indicators of their functional capacity and resistance to mechanical loading. Maximum force reflects ultimate tensile strength, stiffness represents resistance to deformation, deformation characterizes elastic behavior, and absorbed energy indicates the tendon’s ability to withstand and dissipate mechanical energy before failure (23,24). These properties are influenced by tendon morphology, collagen organization, extracellular matrix composition, and molecular and cellular factors governing tissue remodeling (25–28). Despite the well-established role of vitamin D in musculoskeletal health, its specific effects on tendon biomechanics remain insufficiently investigated, particularly beyond stiffness and across different experimental models. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of an eight-week vitamin D supplementation protocol on the biomechanical properties of the Achilles tendon in male Wistar rats. It was hypothesized that vitamin D supplementation would lead to improvements in tendon stiffness, tensile strength, and overall mechanical resilience.

2. Methods

In this experimental study, 30 male Wistar rats (aged 2–3 months, initial body mass 180–230 g) obtained from the Royan Institute (Tehran, Iran) were housed at Qom University of Medical Sciences. Animals were acclimatized for one week in polycarbonate cages under controlled environmental conditions (22 °C, 12:12 h light–dark cycle) with ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Rats were randomly allocated into three groups (n = 10 per group): control, paraffin (vehicle), and vitamin D₃ supplementation.

The vitamin D₃ group received 500 IU/kg body weight (equivalent to 12.5 μg/kg), dissolved in paraffin oil (1.5 mg/kg), administered via oral gavage three times per week for eight weeks (29,30). The paraffin group received the vehicle only, while the control group received no intervention. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals at Qom University of Medical Sciences and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Physical Education and Sport Sciences Research Institute (approval code: IR.SSRI.REC.2312.2570).

Twenty-four hours after completion of the intervention period, rats were anesthetized using ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (80 mg/kg). The Achilles tendons were carefully excised, placed in Falcon tubes to prevent dehydration, and subjected to biomechanical testing. Tendon mechanical properties were assessed using a Santam® tensile testing machine, and stress–strain curves along with rupture loads were recorded using the associated software. Descriptive statistics were calculated and are reported as means and standard deviations. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test. Between-group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the level of statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software.

3. Results

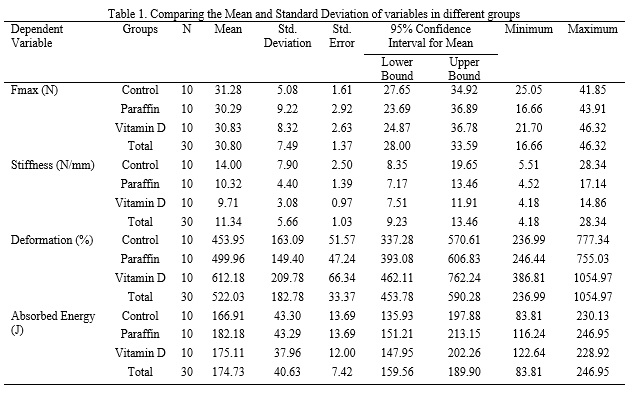

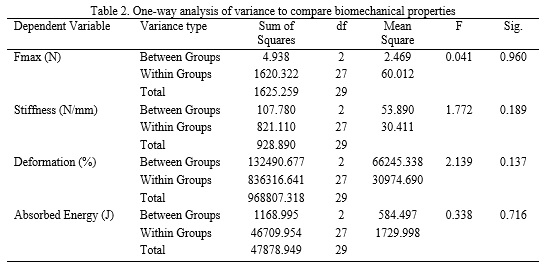

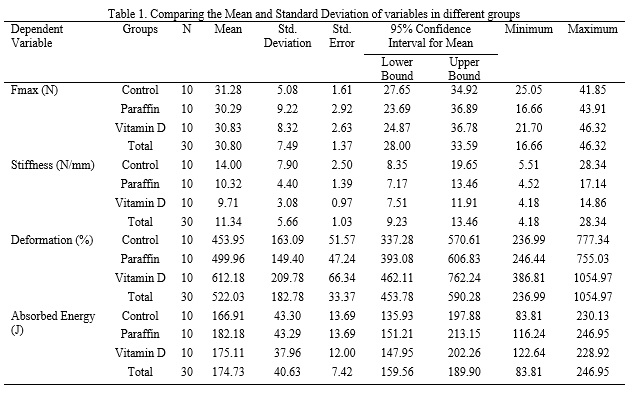

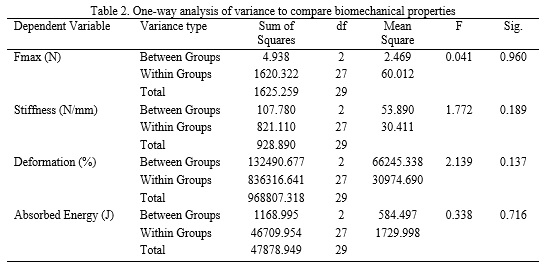

The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed normal data distribution, and Levene’s test indicated homogeneity of variances, thereby satisfying the assumptions for ANOVA. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant effects of vitamin D supplementation on Achilles tendon Fmax, stiffness, absorbed energy, or deformation (p > 0.05; Tables 1 and 2).

1. Introduction

Dietary supplements—defined as nutrients or bioactive compounds used to enhance health or performance beyond what is typically achieved through a standard diet—are widely consumed by both athletes and the general population (1–3). Athletes commonly use supplements not only for direct performance enhancement but also for indirect benefits such as supporting training adaptations, optimizing body composition, facilitating injury recovery, and improving mood and well-being. Over the past two decades, supplement use has increased substantially and now includes a broad range of products, including carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, minerals, herbs, and plant-derived extracts (1,4–12). Vitamin D, a secosteroid prohormone and precursor of the active metabolite calcitriol, plays a central role in calcium–phosphate homeostasis, bone metabolism, skeletal muscle function, and the modulation of inflammatory responses. It has been shown to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), while upregulating the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10). In addition, vitamin D promotes cytoprotective effects in tenocytes through activation of ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, mechanisms that may contribute to tendon repair and tissue homeostasis (13–18). Previous evidence suggests that vitamin D supplementation may enhance tendon strength, stimulate collagen synthesis, and support extracellular matrix integrity, particularly in populations exposed to high mechanical loads, such as athletes, or in aging individuals, potentially accelerating recovery following tendon injury (19–22).

The biomechanical properties of tendons—including maximum force (Fmax), stiffness, deformation, and absorbed energy—are key indicators of their functional capacity and resistance to mechanical loading. Maximum force reflects ultimate tensile strength, stiffness represents resistance to deformation, deformation characterizes elastic behavior, and absorbed energy indicates the tendon’s ability to withstand and dissipate mechanical energy before failure (23,24). These properties are influenced by tendon morphology, collagen organization, extracellular matrix composition, and molecular and cellular factors governing tissue remodeling (25–28). Despite the well-established role of vitamin D in musculoskeletal health, its specific effects on tendon biomechanics remain insufficiently investigated, particularly beyond stiffness and across different experimental models. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of an eight-week vitamin D supplementation protocol on the biomechanical properties of the Achilles tendon in male Wistar rats. It was hypothesized that vitamin D supplementation would lead to improvements in tendon stiffness, tensile strength, and overall mechanical resilience.

2. Methods

In this experimental study, 30 male Wistar rats (aged 2–3 months, initial body mass 180–230 g) obtained from the Royan Institute (Tehran, Iran) were housed at Qom University of Medical Sciences. Animals were acclimatized for one week in polycarbonate cages under controlled environmental conditions (22 °C, 12:12 h light–dark cycle) with ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Rats were randomly allocated into three groups (n = 10 per group): control, paraffin (vehicle), and vitamin D₃ supplementation.

The vitamin D₃ group received 500 IU/kg body weight (equivalent to 12.5 μg/kg), dissolved in paraffin oil (1.5 mg/kg), administered via oral gavage three times per week for eight weeks (29,30). The paraffin group received the vehicle only, while the control group received no intervention. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals at Qom University of Medical Sciences and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Physical Education and Sport Sciences Research Institute (approval code: IR.SSRI.REC.2312.2570).

Twenty-four hours after completion of the intervention period, rats were anesthetized using ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (80 mg/kg). The Achilles tendons were carefully excised, placed in Falcon tubes to prevent dehydration, and subjected to biomechanical testing. Tendon mechanical properties were assessed using a Santam® tensile testing machine, and stress–strain curves along with rupture loads were recorded using the associated software. Descriptive statistics were calculated and are reported as means and standard deviations. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test. Between-group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the level of statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software.

3. Results

The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed normal data distribution, and Levene’s test indicated homogeneity of variances, thereby satisfying the assumptions for ANOVA. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant effects of vitamin D supplementation on Achilles tendon Fmax, stiffness, absorbed energy, or deformation (p > 0.05; Tables 1 and 2).

4. Discussion

In the present study, mean maximum force (Fmax) values did not differ significantly between groups, indicating that vitamin D supplementation does not enhance ultimate tendon strength in healthy animals. This finding is consistent with earlier work by Simonsen et al. (1995) and Sommer (1987), who demonstrated that mechanical loading is the primary determinant of tendon strength once nutritional requirements are met, with dietary factors exerting only a limited influence under normal conditions (31,32). In this context, vitamin D appears to act in a permissive rather than an augmentative manner. In contrast, Angeline et al. (2014) reported reduced Fmax and impaired healing in vitamin D–deficient rotator cuff models, while Min et al. (2019) observed restored collagen type I synthesis and increased tenocyte proliferation in vitro following vitamin D exposure (17,33). These discrepancies are likely attributable to differences in baseline vitamin D status, the presence of tissue injury, and experimental design, supporting the notion that supplementation does not confer additional tensile strength benefits in the absence of deficiency or structural damage.

Similarly, no significant changes in Achilles tendon stiffness were observed following vitamin D supplementation. The slight, non-significant reduction in stiffness in the vitamin D group may reflect minimal biological variability, such as subtle changes in extracellular matrix hydration or collagen cross-linking, rather than true mechanical adaptation. These findings align with those of Kubo et al. (2001), who reported no stiffness alterations following short-term interventions in the absence of mechanical loading (34). Conversely, studies by Tarantino et al. (2024) and Dougherty et al. (2016) demonstrated increased collagen content and reduced matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression in vitamin D–deficient conditions (20,35), suggesting that supplementation alone is insufficient to induce measurable biomechanical remodeling in healthy tendon tissue.

Although the vitamin D group exhibited the highest mean deformation values, these differences did not reach statistical significance. This trend may indicate a slight increase in tendon compliance or viscoelastic behavior; however, given the absence of concomitant changes in Fmax or stiffness, it is more likely attributable to normal biological variability rather than a meaningful adaptive response. Huang et al. (2004) similarly reported non-significant changes in deformation following mild interventions in healthy tendon models (24). In contrast, Guan et al. (2022) observed reduced deformation in osteoporotic models following vitamin D supplementation (21), further supporting the hypothesis that vitamin D primarily exerts protective or restorative effects in compromised tissues rather than enhancing mechanical properties in healthy tendons.

Absorbed energy, a measure of tendon toughness, also did not differ significantly among groups. This finding is consistent with previous animal studies demonstrating stable energy absorption in the absence of prolonged overload, injury, or pathological conditions (32). While Min et al. (2019) and Kim et al. (2022) reported that vitamin D can enhance extracellular matrix integrity at the cellular level (17,18), studies by Huang et al. (2004) and Sommer (1987) emphasized that changes in absorbed energy are more strongly influenced by mechanical loading magnitude and rate than by nutritional supplementation in healthy animals (24,31). It is therefore plausible that molecular or histological alterations induced by vitamin D require longer intervention periods or the presence of injury or deficiency to translate into detectable biomechanical changes. Overall, the absence of significant effects across all measured biomechanical parameters—Fmax, stiffness, deformation, and absorbed energy—suggests that vitamin D supplementation does not provide additive mechanical benefits to structurally intact and physiologically sufficient tendons. These findings underscore the context-dependent nature of vitamin D’s role in tendon biomechanics, with its influence becoming more apparent under conditions of deficiency, inflammation, or tissue damage, where it modulates collagen synthesis, cellular proliferation, and inflammatory pathways (20,35). In contrast, in healthy tendons, structural and functional properties may already operate near an optimal plateau, beyond which additional vitamin D supplementation yields no measurable biomechanical enhancement.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was conducted in compliance with the standards of research ethics and the protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Physical Education and Sport Sciences with the ethics code IR.SSRI.REC-2312-2570.

Funding

The authors have not received any financial support from any government or private organization or institution.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest associated with this study.

In the present study, mean maximum force (Fmax) values did not differ significantly between groups, indicating that vitamin D supplementation does not enhance ultimate tendon strength in healthy animals. This finding is consistent with earlier work by Simonsen et al. (1995) and Sommer (1987), who demonstrated that mechanical loading is the primary determinant of tendon strength once nutritional requirements are met, with dietary factors exerting only a limited influence under normal conditions (31,32). In this context, vitamin D appears to act in a permissive rather than an augmentative manner. In contrast, Angeline et al. (2014) reported reduced Fmax and impaired healing in vitamin D–deficient rotator cuff models, while Min et al. (2019) observed restored collagen type I synthesis and increased tenocyte proliferation in vitro following vitamin D exposure (17,33). These discrepancies are likely attributable to differences in baseline vitamin D status, the presence of tissue injury, and experimental design, supporting the notion that supplementation does not confer additional tensile strength benefits in the absence of deficiency or structural damage.

Similarly, no significant changes in Achilles tendon stiffness were observed following vitamin D supplementation. The slight, non-significant reduction in stiffness in the vitamin D group may reflect minimal biological variability, such as subtle changes in extracellular matrix hydration or collagen cross-linking, rather than true mechanical adaptation. These findings align with those of Kubo et al. (2001), who reported no stiffness alterations following short-term interventions in the absence of mechanical loading (34). Conversely, studies by Tarantino et al. (2024) and Dougherty et al. (2016) demonstrated increased collagen content and reduced matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression in vitamin D–deficient conditions (20,35), suggesting that supplementation alone is insufficient to induce measurable biomechanical remodeling in healthy tendon tissue.

Although the vitamin D group exhibited the highest mean deformation values, these differences did not reach statistical significance. This trend may indicate a slight increase in tendon compliance or viscoelastic behavior; however, given the absence of concomitant changes in Fmax or stiffness, it is more likely attributable to normal biological variability rather than a meaningful adaptive response. Huang et al. (2004) similarly reported non-significant changes in deformation following mild interventions in healthy tendon models (24). In contrast, Guan et al. (2022) observed reduced deformation in osteoporotic models following vitamin D supplementation (21), further supporting the hypothesis that vitamin D primarily exerts protective or restorative effects in compromised tissues rather than enhancing mechanical properties in healthy tendons.

Absorbed energy, a measure of tendon toughness, also did not differ significantly among groups. This finding is consistent with previous animal studies demonstrating stable energy absorption in the absence of prolonged overload, injury, or pathological conditions (32). While Min et al. (2019) and Kim et al. (2022) reported that vitamin D can enhance extracellular matrix integrity at the cellular level (17,18), studies by Huang et al. (2004) and Sommer (1987) emphasized that changes in absorbed energy are more strongly influenced by mechanical loading magnitude and rate than by nutritional supplementation in healthy animals (24,31). It is therefore plausible that molecular or histological alterations induced by vitamin D require longer intervention periods or the presence of injury or deficiency to translate into detectable biomechanical changes. Overall, the absence of significant effects across all measured biomechanical parameters—Fmax, stiffness, deformation, and absorbed energy—suggests that vitamin D supplementation does not provide additive mechanical benefits to structurally intact and physiologically sufficient tendons. These findings underscore the context-dependent nature of vitamin D’s role in tendon biomechanics, with its influence becoming more apparent under conditions of deficiency, inflammation, or tissue damage, where it modulates collagen synthesis, cellular proliferation, and inflammatory pathways (20,35). In contrast, in healthy tendons, structural and functional properties may already operate near an optimal plateau, beyond which additional vitamin D supplementation yields no measurable biomechanical enhancement.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was conducted in compliance with the standards of research ethics and the protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Physical Education and Sport Sciences with the ethics code IR.SSRI.REC-2312-2570.

Funding

The authors have not received any financial support from any government or private organization or institution.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest associated with this study.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/11/30 | Accepted: 2026/01/20 | Published: 2026/02/3

Received: 2025/11/30 | Accepted: 2026/01/20 | Published: 2026/02/3

References

1. Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, Larson-Meyer DE, Peeling P, Phillips SM, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(7):439-55. [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099027]

2. Wardenaar F, van den Dool R, Ceelen I, Witkamp R, Mensink M. Self-reported use and reasons among the general population for using sports nutrition products and dietary supplements. Sports. 2016;4(2):33. [DOI:10.3390/sports4020033]

3. Hijlkema A, Roozenboom C, Mensink M, Zwerver J. The impact of nutrition on tendon health and tendinopathy: a systematic review. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2022;19(1):474-504. [DOI:10.1080/15502783.2022.2104130]

4. Almasi J, Shabazbigian MM. The effect of six weeks of high-intensity interval training with and without coenzyme Q10 supplementation on bench press and squat strength in competitive male bodybuilders. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2025;11(1):80-92. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.11.1.80]

5. Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. The Journal of Nutrition. 2011;141(2):261-6. [DOI:10.3945/jn.110.133025]

6. Fennell D. Determinants of supplement usage. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(5):932-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.031]

7. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M, White E, Giovannucci EL. Trends in dietary supplement use among US adults from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2016;316(14):1464-74. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.14403]

8. Marik PE, Flemmer M. Do dietary supplements have beneficial health effects in industrialized nations: what is the evidence? Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;36(2):159-68. [DOI:10.1177/0148607111416485]

9. Manson JE, Brannon PM, Rosen CJ, Taylor CL. Vitamin D deficiency-is there really a pandemic? The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(19):1817-20. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1608005]

10. Balentine DA, Dwyer JT, Erdman JW Jr, Ferruzzi MG, Gaine PC, Harnly JM, et al. Recommendations on reporting requirements for flavonoids in research. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;101(6):1113-25. [DOI:10.3945/ajcn.113.071274]

11. Dwyer JT, Coates PM, Smith MJ. Dietary supplements: regulatory challenges and research resources. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):41. [DOI:10.3390/nu10010041]

12. Kerksick CM, Wilborn CD, Roberts MD, Smith-Ryan A, Kleiner SM, Jäger R, et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2018;15(1):38. [DOI:10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y]

13. Jeon SM, Shin EA. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2018;50(4):1-14. [DOI:10.1038/s12276-018-0038-9]

14. Wintermeyer E, Ihle C, Ehnert S, Stöckle U, Ochs G, de Zwart P, et al. Crucial role of vitamin D in the musculoskeletal system. Nutrients. 2016;8(6):319. [DOI:10.3390/nu8060319]

15. Millar NL, Murrell GAC, McInnes IB. Inflammatory mechanisms in tendinopathy-towards translation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2017;13(2):110-22. [DOI:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.213]

16. Khoo AL, Chai LYA, Koenen HJPM, Oosting M, Steinmeyer A, Zuegel U, et al. Vitamin D(3) down-regulates proinflammatory cytokine response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis through pattern recognition receptors while inducing protective cathelicidin production. Cytokine. 2011;55(2):294-300. [DOI:10.1016/j.cyto.2011.04.016]

17. Min K, Lee JM, Kim MJ, Jung SY, Kim KS, Lee S, et al. Restoration of cellular proliferation and characteristics of human tenocytes by vitamin D. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2019;37(10):2241-8. [DOI:10.1002/jor.24352]

18. Kim DS, Kim JH, Baek SW, Lee JK, Park SY, Choi B, et al. Controlled vitamin D delivery with injectable hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel for restoration of tendinopathy. Journal of Tissue Engineering. 2022;13:20417314221122089. [DOI:10.1177/20417314221122089]

19. Soltani M, Fatahi A, Yousefian Molla R. The effect of increasing running speed on three-dimensional changes of lower limb joint angles in open motor chain and swing phase. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2022;8(3):232-46. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.8.3.232]

20. Tarantino D, Mottola R, Sirico F, Corrado B, Ruosi C, Saggini R, et al. Exploring the impact of vitamin D on tendon health: a comprehensive review. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. 2024;35(3):143-52. [DOI:10.1515/jbcpp-2024-0061]

21. Guan Z, Liu S, Luo L, Zhang Q, Tao K. The role of vitamin D on rotator cuff tear with osteoporosis. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022;13. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2022.847401]

22. Mohammad Zaheri R, Majlesi M, Fatahi A. Impact of lower-limb fatigue on kinetic risk factors for ACL injury during post-spike landings in volleyball athletes. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2026;11(4):466-84. [DOI:10.61882/JSportBiomech.11.4.466]

23. Buschmann J, Bürgisser GM. Biomechanics of tendons and ligaments: tissue reconstruction and regeneration. Woodhead Publishing; 2017. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-08-100489-0.00003-X]

24. Huang TF, Perry SM, Soslowsky LJ. The effect of overuse activity on Achilles tendon in an animal model: a biomechanical study. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2004;32(3):336-41. [DOI:10.1023/B:ABME.0000017537.26426.76]

25. Shamsehkohan P, Sadeghi H. Overview of the mechanical function of tissue cells affecting human movement. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2016;5(4):271-81.

26. Peterson DR, Bronzino JD. Biomechanics: principles and applications. 2nd ed. CRC Press; 2007. [DOI:10.1201/9781420008197]

27. Theret DP, Levesque MJ, Sato M, Nerem RM, Wheeler LT. The application of a homogeneous half-space model in the analysis of endothelial cell micropipette measurements. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1988;110(3):190-9. [DOI:10.1115/1.3108430]

28. Mohammad Pour Koli M, Fatahi A. Modern approaches in sport biomechanics: a review paper. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2024;9(4):284-300. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.9.4.284]

29. Nourozi A, Shariati M. Protective effect of vitamin D on spermatogenesis and testicular tissue changes in adult rats treated with thioacetamide. Alborz Health. 2020;9(2):107. [DOI:10.29252/aums.9.2.107]

30. Mehdipoor M, Damirchi A, Razavi Tousi SMT, Babaei P. Concurrent vitamin D supplementation and exercise training improve cardiac fibrosis via TGF-β/Smad signaling in myocardial infarction model of rats. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2021;77(1):75-84. [DOI:10.1007/s13105-020-00778-6]

31. Sommer HM. The biomechanical and metabolic effects of a running regime on the Achilles tendon in the rat. International Orthopaedics. 1987;11(1):71-5. [DOI:10.1007/BF00266061]

32. Simonsen EB, Klitgaard H, Bojsen-Møller F. The influence of strength training, swim training and ageing on the Achilles tendon and m. soleus of the rat. Journal of Sports Sciences. 1995;13(4):291-5. [DOI:10.1080/02640419508732242]

33. Angeline ME, Ma R, Pascual-Garrido C, Voigt C, Deng XH, Warren RF, et al. Effect of diet-induced vitamin D deficiency on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;42(1):27-34. [DOI:10.1177/0363546513505421]

34. Kubo K, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. Effects of different duration isometric contractions on tendon elasticity in human quadriceps muscles. The Journal of Physiology. 2001;536(Pt 2):649-55. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0649c.xd]

35. Dougherty KA, Dilisio MF, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D and the immunomodulation of rotator cuff injury. Journal of Inflammation Research. 2016;9:123-31. [DOI:10.2147/JIR.S106206]

36. Chen J, Tang Z, Slominski AT, Li W, Żmijewski MA, Liu Y, et al. Vitamin D and its analogs as anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2020;207:112738. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112738]

37. Dhesi JK, Jackson SHD, Bearne LM, Moniz C, Hurley MV, Swift CG, et al. Vitamin D supplementation improves neuromuscular function in older people who fall. Age and Ageing. 2004;33(6):589-95. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afh209]

38. Żebrowska A, Sadowska-Krępa E, Stanula A, Waśkiewicz Z, Łakomy O, Bezuglov E, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum total 25(OH) levels and biochemical markers of skeletal muscles in runners. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2020;17(1):18. [DOI:10.1186/s12970-020-00347-8]

39. Barker T, Henriksen VT, Rogers VE, Aguirre D, Trawick RH, Lynn Rasmussen G, et al. Vitamin D deficiency associates with γ-tocopherol and quadriceps weakness but not inflammatory cytokines in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. Redox Biology. 2014;2:466-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.024]

40. Schwartz Z, Schlader DL, Ramirez V, Kennedy MB, Boyan BD. Effects of vitamin D metabolites on collagen production and cell proliferation of growth zone and resting zone cartilage cells in vitro. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1989;4(2):199-207. [DOI:10.1002/jbmr.5650040211]

41. Ulreich N, Kainberger F, Huber W, Nehrer S. Die Achillessehne im Sport. Der Radiologe. 2002;42:811-7. [DOI:10.1007/s00117-002-0800-8]

42. Nourissat G, Houard X, Sellam J, Duprez D, Berenbaum F. Use of autologous growth factors in aging tendon and chronic tendinopathy. Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Edition). 2013;5(3):911-21. [DOI:10.2741/E670]

43. Oatis CA. Kinesiology: the mechanics and pathomechanics of human movement. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

44. Hamill J, Knutzen K, Derrick T. Biomechanical basis of human movement. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015.

45. Chel V, Wijnhoven HAH, Smit JH, Ooms M, Lips P. Efficacy of different doses and time intervals of oral vitamin D supplementation with or without calcium in elderly nursing home residents. Osteoporosis International. 2008;19(5):663-71. [DOI:10.1007/s00198-007-0538-2]

46. Zittermann A, Trummer C, Theiler-Schwetz V, Pilz S. Long-term supplementation with 3200 to 4000 IU of vitamin D daily and adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Nutrition. 2023;62(4):1833-44. [DOI:10.1007/s00394-023-03124-w]

47. Langberg H, Skovgaard D, Petersen LJ, Bülow J, Kjær M. Type I collagen synthesis and degradation in peritendinous tissue after exercise determined by microdialysis in humans. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;521(Pt 1):299-306. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00299.x]

48. Heinemeier K, Langberg H, Olesen JL, Kjær M. Role of TGF-β1 in relation to exercise-induced type I collagen synthesis in human tendinous tissue. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;95(6):2390-7. [DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00403.2003]

49. Koenen K, Knepper I, Klodt M, Osterberg A, Stratos I, Mittlmeier T, et al. Sprint interval training induces a sexual dimorphism but does not improve peak bone mass in young and healthy mice. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:44047. [DOI:10.1038/srep44047]

50. Kubo K, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. Effects of resistance and stretching training programmes on the viscoelastic properties of human tendon structures in vivo. The Journal of Physiology. 2002;538(Pt 1):219-26. [DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012703]

51. Woo SL, Gomez MA, Amiel D, Ritter MA, Gelberman RH, Akeson WH. The effects of exercise on the biomechanical and biochemical properties of swine digital flexor tendons. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1981;103(1):51-6. [DOI:10.1115/1.3138246]

52. Magnusson SP, Kjær M. Region-specific differences in Achilles tendon cross-sectional area in runners and non-runners. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;90(5-6):549-53. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-003-0865-8]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |