Volume 12, Issue 2 (9-2026)

J Sport Biomech 2026, 12(2): 338-356 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mahdizadeh A, Sadeghi H, Tehrani P. Effects of Aquatic Balance–Strength Training on Direction‑Specific Changes in Center of Pressure Velocity and Displacement Amplitude in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis. J Sport Biomech 2026; 12 (2) :338-356

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-494-en.html

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-494-en.html

1- Department of Sports Biomechanics, CT.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Sport Biomechanics and Injuries, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, Kharazmi University Tehran, Iran. & Department of Sport Biomechanics and Rehabilitation, Kinesiology Research Center, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Mechanical Engineering, CT.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Sport Biomechanics and Injuries, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, Kharazmi University Tehran, Iran. & Department of Sport Biomechanics and Rehabilitation, Kinesiology Research Center, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Mechanical Engineering, CT.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Postmenopausal women, Aquatic exercise, Center of pressure, Postural control

Full-Text [PDF 2282 kb]

(30 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (53 Views)

Full-Text: (13 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a prevalent skeletal disorder among older adults, characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue (1,2). In postmenopausal women, it is frequently accompanied by reductions in muscle strength and sensorimotor function, which collectively increase the risk of falls and fractures (3–6). Impaired postural control is a major contributor to this elevated risk, and center of pressure (COP)–derived metrics are widely used as sensitive indicators of static balance performance (7–11). Among these variables, mean COP velocity (MV-COP) is considered particularly responsive because it reflects the overall magnitude of sway and the intensity of neuromuscular control activity, whereas COP displacement amplitude (DA-COP) provides complementary information regarding the spatial extent of instability along the anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) axes (12–15).

Although several land-based randomized trials have demonstrated improvements in postural outcomes following balance, strength, or combined interventions in women with osteoporosis, the available evidence is limited by heterogeneity in exercise protocols, inconsistent selection of COP variables, and insufficient directional analysis. In addition, certain land-based balance tasks may impose mechanical and postural control demands that challenge individuals with compromised skeletal integrity, particularly under reduced base-of-support conditions (16,17). Aquatic exercise offers a potentially advantageous alternative due to buoyancy-mediated unloading, multidirectional viscous resistance, and continuous low-amplitude perturbations that may safely stimulate multisensory integration processes (18–22). To date, only one study (Aveiro et al.) has evaluated aquatic training in this population; however, it did not assess COP responses separately in the AP and ML directions under systematically graded stance conditions (23). Consequently, empirical evidence regarding the directional characteristics of COP adaptations following structured aquatic balance–strength training remains limited.

Accordingly, the present study aimed to examine the effects of a 12-week structured aquatic balance–strength training program, incorporating principles of the Otago Exercise Program and ROPE methodology, on MV-COP and DA-COP in the AP and ML directions during progressively challenging static stance tasks in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

2. Methods

This semi-experimental pre–post controlled study included 24 postmenopausal women aged 50–65 years with osteoporosis (T-score ≤ −2.5 at the femoral neck and L1–L4). The sample size was determined a priori using G*Power (α = 0.05, power = 0.80, effect size = 0.35). Eligible participants were identified from DXA records in eastern Tehran and selected using computer-generated random numbers. After orthopedic screening, participants were randomly assigned, via concealed sealed envelopes prepared by an independent researcher, to either an aquatic training group or a non-exercising control group.

Inclusion criteria were female sex, age 50–65 years, more than five years postmenopause, and independent ambulation. Exclusion criteria included cardiovascular, pulmonary, neuromuscular, oncologic, or severe arthritic disease; major visual, vestibular, or sensory deficits; limb-length discrepancy; use of internal orthoses; regular exercise within the previous six months; substantial fear of water; and use of medications or dietary regimens affecting bone metabolism. The screening physician, force-plate operator, and data analysts were blinded to group allocation. Static balance was assessed using a Kistler 9260AA6 force plate during four 60-second quiet-stance tasks: two-legged stance with eyes open (TLEO) and closed (TLEC), and semi-tandem stance with eyes open (STEO) and closed (STEC), each performed three times. Foot position was self-selected in TLEO and TLEC; in STEO and STEC, the dominant foot was positioned posteriorly in a standardized semi-tandem configuration (13,14,24,25). Data were sampled at 100 Hz, low-pass filtered (fourth-order Butterworth, 10 Hz), and the first 10 seconds of each trial were discarded (26–28).

MV-COP (AP and ML) was calculated as sway path length divided by trial duration. DA-COP was defined as the maximal excursion around the mean COP in each axis. For each condition, the mean of the three trials was used for analysis. The intervention consisted of 12 weeks of aquatic balance–strength training (three sessions per week, 50–75 minutes per session), adapted from the Otago and ROPE programs, and performed in chest-deep water (29,30). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21 with paired t-tests and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with baseline values entered as covariates (p < 0.05).

3. Results

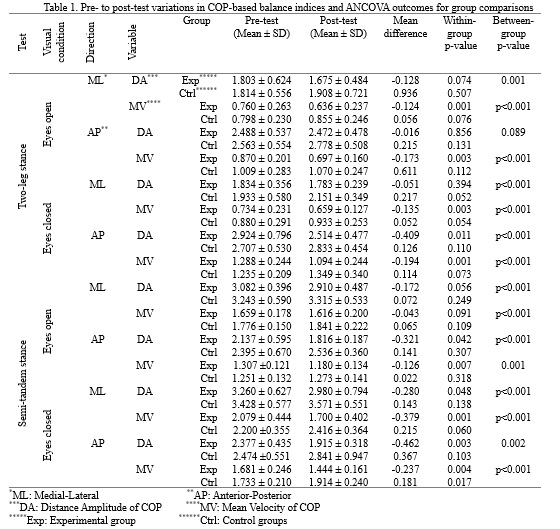

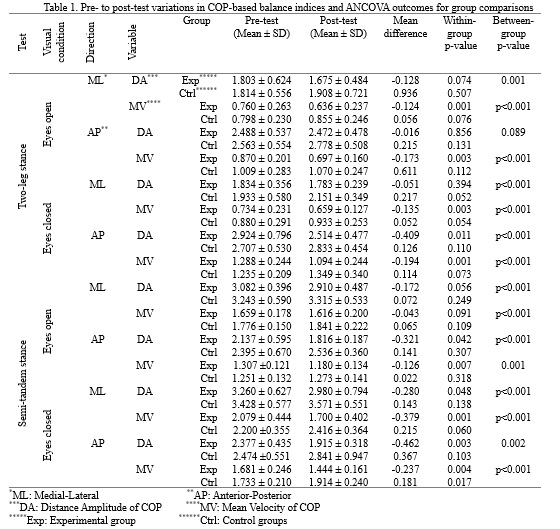

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and change scores for balance parameters at the pre- and post-test assessments. Negative values indicate improvement, as reduced center-of-pressure sway reflects enhanced postural stability. In addition, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) results controlling for baseline values are presented to enable a more rigorous comparison between groups. Within-group analyses showed that the aquatic training group demonstrated significant improvements across a wide range of COP-based indices, whereas the control group exhibited minimal changes or slight deterioration. In the training group, MV-COP decreased significantly (p < 0.05) in the AP direction across all four tasks (TLEO, TLEC, STEO, STEC) and in the ML direction during TLEO, TLEC, and STEC. The only non-significant MV-COP change was observed in the ML direction during STEO. DA-COP also decreased significantly during STEC in both AP and ML directions, and during STEO and TLEC in the AP direction. Changes in TLEO (AP and ML) and in STEO and TLEC (ML) were not statistically significant. In contrast, the control group showed no significant pre–post improvements. The only significant change was an increase in MV-COP in the AP direction during STEC (p = 0.017), indicating reduced stability under the most challenging condition. All other COP variables remained statistically unchanged (p > 0.05).

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a prevalent skeletal disorder among older adults, characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue (1,2). In postmenopausal women, it is frequently accompanied by reductions in muscle strength and sensorimotor function, which collectively increase the risk of falls and fractures (3–6). Impaired postural control is a major contributor to this elevated risk, and center of pressure (COP)–derived metrics are widely used as sensitive indicators of static balance performance (7–11). Among these variables, mean COP velocity (MV-COP) is considered particularly responsive because it reflects the overall magnitude of sway and the intensity of neuromuscular control activity, whereas COP displacement amplitude (DA-COP) provides complementary information regarding the spatial extent of instability along the anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) axes (12–15).

Although several land-based randomized trials have demonstrated improvements in postural outcomes following balance, strength, or combined interventions in women with osteoporosis, the available evidence is limited by heterogeneity in exercise protocols, inconsistent selection of COP variables, and insufficient directional analysis. In addition, certain land-based balance tasks may impose mechanical and postural control demands that challenge individuals with compromised skeletal integrity, particularly under reduced base-of-support conditions (16,17). Aquatic exercise offers a potentially advantageous alternative due to buoyancy-mediated unloading, multidirectional viscous resistance, and continuous low-amplitude perturbations that may safely stimulate multisensory integration processes (18–22). To date, only one study (Aveiro et al.) has evaluated aquatic training in this population; however, it did not assess COP responses separately in the AP and ML directions under systematically graded stance conditions (23). Consequently, empirical evidence regarding the directional characteristics of COP adaptations following structured aquatic balance–strength training remains limited.

Accordingly, the present study aimed to examine the effects of a 12-week structured aquatic balance–strength training program, incorporating principles of the Otago Exercise Program and ROPE methodology, on MV-COP and DA-COP in the AP and ML directions during progressively challenging static stance tasks in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

2. Methods

This semi-experimental pre–post controlled study included 24 postmenopausal women aged 50–65 years with osteoporosis (T-score ≤ −2.5 at the femoral neck and L1–L4). The sample size was determined a priori using G*Power (α = 0.05, power = 0.80, effect size = 0.35). Eligible participants were identified from DXA records in eastern Tehran and selected using computer-generated random numbers. After orthopedic screening, participants were randomly assigned, via concealed sealed envelopes prepared by an independent researcher, to either an aquatic training group or a non-exercising control group.

Inclusion criteria were female sex, age 50–65 years, more than five years postmenopause, and independent ambulation. Exclusion criteria included cardiovascular, pulmonary, neuromuscular, oncologic, or severe arthritic disease; major visual, vestibular, or sensory deficits; limb-length discrepancy; use of internal orthoses; regular exercise within the previous six months; substantial fear of water; and use of medications or dietary regimens affecting bone metabolism. The screening physician, force-plate operator, and data analysts were blinded to group allocation. Static balance was assessed using a Kistler 9260AA6 force plate during four 60-second quiet-stance tasks: two-legged stance with eyes open (TLEO) and closed (TLEC), and semi-tandem stance with eyes open (STEO) and closed (STEC), each performed three times. Foot position was self-selected in TLEO and TLEC; in STEO and STEC, the dominant foot was positioned posteriorly in a standardized semi-tandem configuration (13,14,24,25). Data were sampled at 100 Hz, low-pass filtered (fourth-order Butterworth, 10 Hz), and the first 10 seconds of each trial were discarded (26–28).

MV-COP (AP and ML) was calculated as sway path length divided by trial duration. DA-COP was defined as the maximal excursion around the mean COP in each axis. For each condition, the mean of the three trials was used for analysis. The intervention consisted of 12 weeks of aquatic balance–strength training (three sessions per week, 50–75 minutes per session), adapted from the Otago and ROPE programs, and performed in chest-deep water (29,30). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21 with paired t-tests and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with baseline values entered as covariates (p < 0.05).

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and change scores for balance parameters at the pre- and post-test assessments. Negative values indicate improvement, as reduced center-of-pressure sway reflects enhanced postural stability. In addition, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) results controlling for baseline values are presented to enable a more rigorous comparison between groups. Within-group analyses showed that the aquatic training group demonstrated significant improvements across a wide range of COP-based indices, whereas the control group exhibited minimal changes or slight deterioration. In the training group, MV-COP decreased significantly (p < 0.05) in the AP direction across all four tasks (TLEO, TLEC, STEO, STEC) and in the ML direction during TLEO, TLEC, and STEC. The only non-significant MV-COP change was observed in the ML direction during STEO. DA-COP also decreased significantly during STEC in both AP and ML directions, and during STEO and TLEC in the AP direction. Changes in TLEO (AP and ML) and in STEO and TLEC (ML) were not statistically significant. In contrast, the control group showed no significant pre–post improvements. The only significant change was an increase in MV-COP in the AP direction during STEC (p = 0.017), indicating reduced stability under the most challenging condition. All other COP variables remained statistically unchanged (p > 0.05).

Between-group ANCOVA, controlling for baseline values, demonstrated significant intervention effects across nearly all COP outcomes. The only exception was DA-COP in the AP direction during the TLEO test, which did not reach statistical significance. For all other stance conditions, directions, and variables, post-test values were significantly better in the aquatic training group than in the control group (p < 0.05). The pattern of adjusted means confirmed that these improvements were attributable to the aquatic training program rather than to baseline differences or spontaneous variation.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that a 12-week aquatic balance–strength training program, based on Otago and ROPE principles, produced meaningful improvements in COP-based postural stability in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. The most pronounced effects were observed in MV-COP, particularly under challenging stance conditions and along the AP axis. These findings support prior evidence suggesting that velocity-related COP measures are more sensitive to early neuromuscular adaptations than spatial sway metrics (31,32). From a neuromechanical perspective, these findings are consistent with current theoretical frameworks. MV-COP reflects rapid sensorimotor processing, reduced response latency, and enhanced anticipatory and reactive postural adjustments—mechanisms that tend to adapt relatively quickly with training (32). In contrast, DA-COP is more closely associated with structural muscle capacity and the ability to generate larger stabilizing torques, which typically require longer intervention periods to improve (13,33). The aquatic environment, characterized by buoyancy-induced unloading and viscous resistance, may further promote frequent, small corrective actions rather than large-amplitude excursions, thereby reinforcing improvements in MV-COP (34,35).

Task-specific patterns highlighted the influence of base of support and dominant balance strategy. The greatest improvements were observed in semi-tandem conditions, particularly STEC, where reduced stability and removal of visual input increase reliance on ankle-dominant control in the sagittal plane. In contrast, two-legged stance tasks elicited smaller changes, likely due to greater involvement of trunk and pelvic strategies and reduced lateral mechanical stimulation in the aquatic environment (36–38). The stronger adaptations in the AP compared with the ML direction are consistent with the primary role of ankle mechanisms in rapid postural regulation (39). Methodologically, the combined assessment of MV-COP and DA-COP across AP and ML directions, together with assessor blinding and direction-specific ANCOVA, strengthens the validity of the findings. Clinically, the results suggest that structured aquatic training may enhance the speed of postural corrections, reduce AP sway under reduced base-of-support conditions, and help mitigate age-related decline in postural control in women with osteoporosis.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Research Ethics Committee of the Kharazmi University Motor Behavior Research Center. Ethical approval for the study was obtained under the code IR‑KHU.KRC.1000.220.

Funding

The authors have not received any financial support from any government or private organization or institution.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, investigation, methodology, data analysis, and manuscript drafting and revision were carried out by Ava Mahdizadeh and Heydar Sadeghi. All authors contributed to the final approval of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest associated with this study.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that a 12-week aquatic balance–strength training program, based on Otago and ROPE principles, produced meaningful improvements in COP-based postural stability in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. The most pronounced effects were observed in MV-COP, particularly under challenging stance conditions and along the AP axis. These findings support prior evidence suggesting that velocity-related COP measures are more sensitive to early neuromuscular adaptations than spatial sway metrics (31,32). From a neuromechanical perspective, these findings are consistent with current theoretical frameworks. MV-COP reflects rapid sensorimotor processing, reduced response latency, and enhanced anticipatory and reactive postural adjustments—mechanisms that tend to adapt relatively quickly with training (32). In contrast, DA-COP is more closely associated with structural muscle capacity and the ability to generate larger stabilizing torques, which typically require longer intervention periods to improve (13,33). The aquatic environment, characterized by buoyancy-induced unloading and viscous resistance, may further promote frequent, small corrective actions rather than large-amplitude excursions, thereby reinforcing improvements in MV-COP (34,35).

Task-specific patterns highlighted the influence of base of support and dominant balance strategy. The greatest improvements were observed in semi-tandem conditions, particularly STEC, where reduced stability and removal of visual input increase reliance on ankle-dominant control in the sagittal plane. In contrast, two-legged stance tasks elicited smaller changes, likely due to greater involvement of trunk and pelvic strategies and reduced lateral mechanical stimulation in the aquatic environment (36–38). The stronger adaptations in the AP compared with the ML direction are consistent with the primary role of ankle mechanisms in rapid postural regulation (39). Methodologically, the combined assessment of MV-COP and DA-COP across AP and ML directions, together with assessor blinding and direction-specific ANCOVA, strengthens the validity of the findings. Clinically, the results suggest that structured aquatic training may enhance the speed of postural corrections, reduce AP sway under reduced base-of-support conditions, and help mitigate age-related decline in postural control in women with osteoporosis.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Research Ethics Committee of the Kharazmi University Motor Behavior Research Center. Ethical approval for the study was obtained under the code IR‑KHU.KRC.1000.220.

Funding

The authors have not received any financial support from any government or private organization or institution.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, investigation, methodology, data analysis, and manuscript drafting and revision were carried out by Ava Mahdizadeh and Heydar Sadeghi. All authors contributed to the final approval of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest associated with this study.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2026/01/4 | Accepted: 2026/02/15 | Published: 2026/02/17

Received: 2026/01/4 | Accepted: 2026/02/15 | Published: 2026/02/17

References

1. Erhan B, Ataker Y. Rehabilitation of patients with osteoporotic fractures. Journal of Clinical Densitometry. 2020;23(4):534-538. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocd.2020.06.006]

2. Frank E. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017;167(12):899. [DOI:10.7326/L17-0489]

3. Berk E, Koca TT, Güzelsoy SS, Nacitarhan V, Demirel A. Evaluation of the relationship between osteoporosis, balance, fall risk, and audiological parameters. Clinical Rheumatology. 2019;38:3261-3268. [DOI:10.1007/s10067-019-04655-6]

4. Miko I, Szerb I, Szerb A, Bender T, Poor G. Effect of a balance-training programme on postural balance, aerobic capacity and frequency of falls in women with osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2018;50(6):542-547. [DOI:10.2340/16501977-2349]

5. Walker MD, Shane E. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;389(21):1979-1991. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp2307353]

6. Miller P, Pannacciulli N, Malouf-Sierra J, Singer A, Czerwiński E, Bone H, et al. Efficacy and safety of denosumab vs. bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women previously treated with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporosis International. 2020;31:181-191. [DOI:10.1007/s00198-019-05233-x]

7. Mollova K, Valeva S, Bekir N, Teneva P, Varlyakov K. Effectiveness of proprioceptive training on postural stability and chronic pain in older women with osteoporosis: a six-month prospective pilot study. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025;10(3):316. [DOI:10.3390/jfmk10030316]

8. Stolzenberg N, Felsenberg D, Belavy D. Postural control is associated with muscle power in post-menopausal women with low bone mass. Osteoporosis International. 2018;29(10):2283-2288. [DOI:10.1007/s00198-018-4599-1]

9. Jorgensen MG. Assessment of postural balance in community-dwelling older adults. Danish Medical Journal. 2014;61(1):B4775.

10. Hewson DJ, Singh NK, Snoussi H, Duchene J. Classification of elderly as fallers and non-fallers using centre of pressure velocity. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2010 Aug 31-Sep 4; Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 3678-3680. [DOI:10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5627649]

11. Dehkordi SS, ShamsehKohan P. Comparison of symmetry in postural sway while maintaining static balance in elderly women with and without poor central stability. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2023;9(1):60-72. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.9.1.60]

12. Rizzato A, Benazzato M, Cognolato M, Grigoletto D, Paoli A, Marcolin G. Different neuromuscular control mechanisms regulate static and dynamic balance: a center-of-pressure analysis in young adults. Human Movement Science. 2023;90:103120. [DOI:10.1016/j.humov.2023.103120]

13. Quijoux F, Nicolaï A, Chairi I, Bargiotas I, Ricard D, Yelnik A, et al. A review of center of pressure (COP) variables to quantify standing balance in elderly people: algorithms and open-access code. Physiological Reports. 2021;9(22):e15067. [DOI:10.14814/phy2.15067]

14. Riemann BL, Piersol K. Intersession reliability of self-selected and narrow stance balance testing in older adults. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;29:1045-1048. [DOI:10.1007/s40520-016-0687-2]

15. Graves M, Snyder K, McFelea J, Szczepanski J, Smith MP, Strobel T, et al. Quantitative measurement of the improvement derived from a 10-month progressive exercise program to improve balance and function in women at increased risk for fragility fractures. Journal of Clinical Densitometry. 2020;23(2):286-293. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocd.2018.06.003]

16. Mineiro L, Zeigelboim BS, dos Santos CF, da Rosa MR, Valderramas S, Gomes ARS. Effects of exercise for older women with osteoporosis: a systematic review. Molecular and Cellular Biomechanics. 2024;21:117-119. [DOI:10.62617/mcb.v21.117]

17. Kumar S, Smith C, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Beck BR, Girgis CM. Exercise for postmenopausal bone health-can we raise the bar? Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2025;23(1):20. [DOI:10.1007/s11914-025-00912-7]

18. Seyedjafari E, Sahebozamani M, Ebrahimipour E. Effect of eight weeks of water exercises in the deep part of the pool on the static balance of elderly men. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2017;12(3):384-393. [DOI:10.21859/sija.12.3.384]

19. Zaravar F, Tamaddon G, Zaravar L, Jahromi MK. The effect of aquatic training and vitamin D3 supplementation on bone metabolism in postmenopausal obese women. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness. 2024;22(2):127-133. [DOI:10.1016/j.jesf.2024.01.002]

20. Deng Y, Tang Z, Yang Z, Chai Q, Lu W, Cai Y, et al. Comparing the effects of aquatic-based exercise and land-based exercise on balance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity. 2024;21(1):13. [DOI:10.1186/s11556-024-00349-4]

21. Appiah-Kubi KO, Galgon A, Tierney R, Lauer R, Wright WG. Concurrent vestibular activation and postural training recalibrate somatosensory, vestibular and gaze stabilization processes. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0292200. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0292200]

22. Hesari AR, Hesari AR, Pirshahid AM. Comparison of musculoskeletal disorders in the upper limbs of male athletes with obese and thin non-athlete males. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2023;7(4):260-269.

23. Aveiro MC, Avila MA, Pereira-Baldon VS, Ceccatto Oliveira ASB, Gramani-Say K, Oishi J, et al. Water-versus land-based treatment for postural control in postmenopausal osteoporotic women: a randomized, controlled trial. Climacteric. 2017;20(5):427-435. [DOI:10.1080/13697137.2017.1325460]

24. Rhea CK, Kiefer AW, Wright WG, Raisbeck LD, Haran FJ. Interpretation of postural control may change due to data processing techniques. Gait and Posture. 2015;41(2):731-735. [DOI:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.01.008]

25. Alsubaie SF, Whitney SL, Furman JM, Marchetti GF, Sienko KH, Sparto PJ. Reliability of postural sway measures of standing balance tasks. Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2018;35(1):11-18. [DOI:10.1123/jab.2017-0322]

26. Gonzalez DRG, Imbiriba LA, Jandre FC. Comparison of body sway measured by a markerless low-cost motion sensor and by a force plate. Research on Biomedical Engineering. 2021;37(3):507-517. [DOI:10.1007/s42600-021-00161-4]

27. Hernandez ME, Snider J, Stevenson C, Cauwenberghs G, Poizner H. A correlation-based framework for evaluating postural control stochastic dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2015;24(5):551-561. [DOI:10.1109/TNSRE.2015.2436344]

28. Huurnink A, Fransz DP, Kingma I, van Dieën JH. Comparison of a laboratory-grade force platform with a Nintendo Wii Balance Board on measurement of postural control in single-leg stance balance tasks. Journal of Biomechanics. 2013;46(7):1392-1395. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.02.018]

29. Chiu H-L, Yeh T-T, Lo Y-T, Liang P-J, Lee S-C. The effects of the Otago Exercise Programme on actual and perceived balance in older adults: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255780. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0255780]

30. Sinaki M. Musculoskeletal rehabilitation in patients with osteoporosis-Rehabilitation of Osteoporosis Program-Exercise (ROPE). Journal für Mineralstoffwechsel. 2010;17(2):60-65.

31. Hill MW, Wdowski MM, Rosicka K, Kay AD, Muehlbauer T. Exploring the relationship of static and dynamic balance with muscle mechanical properties of the lower limbs in healthy young adults. Frontiers in Physiology. 2023;14:1168314. [DOI:10.3389/fphys.2023.1168314]

32. Ruhe A, Fejer R, Walker B. Center of pressure excursion as a measure of balance performance in patients with non-specific low back pain compared to healthy controls: a systematic review of the literature. European Spine Journal. 2011;20(3):358-368. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-010-1543-2]

33. Zemková E, Kováčiková Z. Sport-specific training induced adaptations in postural control and their relationship with athletic performance. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2023;16:1007804. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2022.1007804]

34. Jain PP, Kanase SB, Rainak A, Kanase SB. Effect of aquatic exercises on postural control in elderly population. NeuroQuantology. 2022;20(16):5349.

35. Marinho-Buzelli AR, Rouhani H, Masani K, Verrier MC, Popovic MR. The influence of the aquatic environment on the control of postural sway. Gait and Posture. 2017;51:70-76. [DOI:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.09.009]

36. Board D, Stemper BD, Yoganandan N, Pintar FA, Shender B, Paskoff G. Biomechanics of the aging spine. Biomedical Sciences Instrumentation. 2006;42:1-6.

37. Fransz DP, Huurnink A, de Boode VA, Kingma I, van Dieën JH. The effect of the stability threshold on time to stabilization and its reliability following a single-leg drop jump landing. Journal of Biomechanics. 2016;49(3):496-501. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.12.048]

38. Hong S, Park S. Biomechanical optimization and reinforcement learning provide insight into transition from ankle to hip strategy in human postural control. Scientific Reports. 2025;15(1):13640. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-97637-5]

39. Swanenburg J, de Bruin ED, Stauffacher M, Mulder T, Uebelhart D. Effects of exercise and nutrition on postural balance and risk of falling in elderly people with decreased bone mineral density: randomized controlled trial pilot study. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2007;21(6):523-534. [DOI:10.1177/0269215507075206]

40. Lee Y, Shin S. Effects of the shape of the base of support and dual task execution on postural control. Asian Journal of Kinesiology. 2019;21(1):14-24. [DOI:10.15758/ajk.2019.21.1.14]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |