Volume 11, Issue 4 (3-2026)

J Sport Biomech 2026, 11(4): 360-376 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hedayati Y, Amirseyfaddini M R, Amiri Khorasani M. The Effect of Post-Activation Performance Enhancement Using Ballistic Movements, Heavy Resistance, and Dynamic Stretching on Barbell Balance During the Bench Press. J Sport Biomech 2026; 11 (4) :360-376

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-398-en.html

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-398-en.html

1- Department of Sports Biomechanics, Faculty of physical education and sports Science, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1648 kb]

(210 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1008 Views)

Full-Text: (204 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

Rashedi et al. (2015) introduced the bench press as one of the most common exercises for developing the pectoralis major muscle and noted that performance in this movement is often used to represent maximal upper-extremity strength among athletes (1). In powerlifting competitions, a successful lift is recorded when the barbell reaches its highest point at the end of the concentric phase, with the elbows fully extended and the wrists aligned in a straight line, showing minimal positional deviation (3). Post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) is defined as a physiological phenomenon that occurs following a conditioning contraction stimulus (CC) (7, 8). Ballistic or throwing exercises are characterized by explosively projecting the resistance load into the air (7). According to the criteria set by the World Powerlifting Federation, barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press is a critical factor. If the athlete completes the lift with substantial wrist misalignment, the attempt may be rejected by the judges (3). Therefore, identifying new training methods that can improve an athlete’s ability to maintain barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase is of considerable importance. The present study was designed to address the following question: What is the effect of ballistic, heavy-resistance, and dynamic stretching warm-up protocols on barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press in male students?

2. Methods

Eighteen male students (mean age: 23.8 ± 1.3 years; height: 174.4 ± 3.36 cm; body mass: 74.4 ± 3.8 kg), each with at least one year of training experience, participated in the study. Following the 1RM assessment session, participants were randomly assigned to three groups (A, B, and C) according to the protocol proposed by Amiri Khorasani and Gulik (2015) (17). Testing was conducted on three separate days, with at least 48 hours of recovery from heavy activity between sessions. Each evaluation included a general warm-up followed by one of the specific warm-up protocols: ballistic, heavy-resistance, or dynamic stretching of the primary muscles. After completing the assigned warm-up protocol, participants rested for 8 minutes. Subsequently, eight passive reflective markers were attached to anatomical landmarks (lateral tip of the acromion, lateral epicondyle of the elbow, and styloid process of the ulna). In addition, two markers were placed on the barbell, 0.2 m apart (2). Participants then performed a 1RM bench press within the calibrated volume of the 3D motion analysis system. Elbow joint angles and wrist positions were recorded. Barbell balance assessment was conducted as follows. The maximum elbow extension angle at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press was identified. At this angle, the vertical (Z-axis) position of both wrists was determined. The absolute difference between the vertical coordinates of the right and left wrists was calculated and defined as the barbell balance.

3. Results

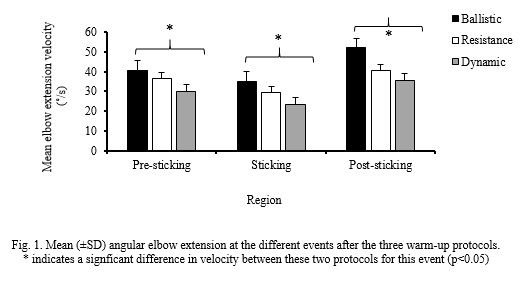

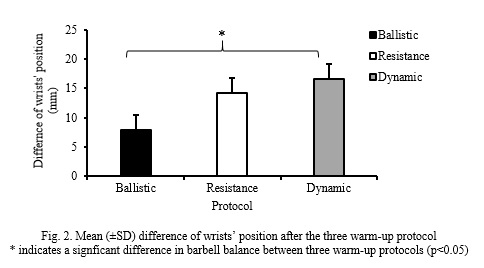

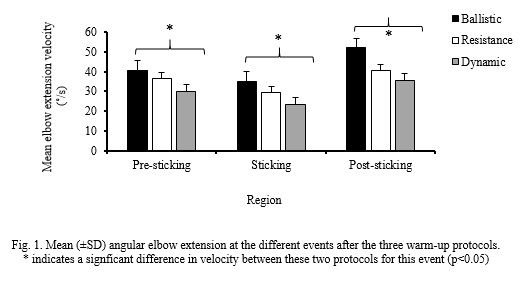

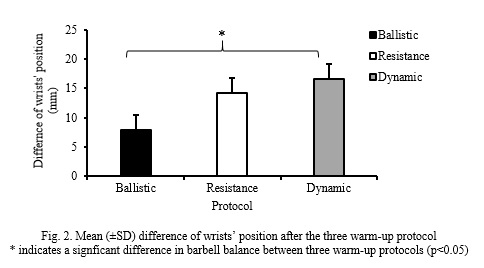

The angular velocity of elbow extension was also affected across the different events. A significant effect was observed at Vmax1, Vmin, and Vmax2 (F = 8.9, p = 0.013, η² = 0.32). Post hoc comparisons revealed that angular velocity was higher following the ballistic warm-up protocol compared with the dynamic stretching protocol at all events (Fig. 1). In addition, after the ballistic warm-up protocol, a significant improvement in barbell balance was observed compared with the other two protocols (F = 20.2, p = 0.001, η² = 0.44). Specifically, participants demonstrated better balance maintenance and the lowest difference in wrist positions following the ballistic protocol. Although the heavy-resistance warm-up protocol produced better barbell balance compared with the dynamic stretching protocol, the difference was not statistically significant (F = 1.21, p = 0.85, η² = 0.11) (Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of different warm-up protocols—ballistic, heavy-resistance, and dynamic stretching—on barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press. The main findings were that elbow extension velocity was higher at Vmax1, Vmin, and Vmax2 following the ballistic warm-up compared with the other two protocols. Furthermore, barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase was significantly better after the ballistic protocol than after either heavy-resistance or dynamic stretching. This enhancement in performance is most likely attributed to post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) (2), which, as suggested by Blazevich and Babault (2019), becomes substantive only after several minutes (21). Several mechanisms may explain the observed improvements in bench press performance following ballistic warm-up. The rapid downward and upward phases of the ballistic bench press may stimulate the stretch-shortening cycle with minimal amortization time between eccentric and concentric actions, thereby maximizing the use of stored elastic energy (22). Additionally, ballistic warm-up may enhance potentiation of contractile elements and increase activation of the pectoral and deltoid muscles, the prime movers in the bench press (4). Another possible mechanism is that during ballistic contractions, the threshold for motor unit recruitment is lower than during slower, ramped contractions (22, 23). These findings provide coaches and athletes, particularly in powerlifting, with a practical and accessible strategy to optimize 1RM bench press performance. Practitioners may consider prescribing ballistic warm-up protocols before maximal bench press attempts.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sport Sciences and Health, University of Tehran (IR.UT.SPORT.REC.1402.136).

Funding

This research did not receive any financial support from the government, private, or non-profit organizations.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this article.

1. Introduction

Rashedi et al. (2015) introduced the bench press as one of the most common exercises for developing the pectoralis major muscle and noted that performance in this movement is often used to represent maximal upper-extremity strength among athletes (1). In powerlifting competitions, a successful lift is recorded when the barbell reaches its highest point at the end of the concentric phase, with the elbows fully extended and the wrists aligned in a straight line, showing minimal positional deviation (3). Post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) is defined as a physiological phenomenon that occurs following a conditioning contraction stimulus (CC) (7, 8). Ballistic or throwing exercises are characterized by explosively projecting the resistance load into the air (7). According to the criteria set by the World Powerlifting Federation, barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press is a critical factor. If the athlete completes the lift with substantial wrist misalignment, the attempt may be rejected by the judges (3). Therefore, identifying new training methods that can improve an athlete’s ability to maintain barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase is of considerable importance. The present study was designed to address the following question: What is the effect of ballistic, heavy-resistance, and dynamic stretching warm-up protocols on barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press in male students?

2. Methods

Eighteen male students (mean age: 23.8 ± 1.3 years; height: 174.4 ± 3.36 cm; body mass: 74.4 ± 3.8 kg), each with at least one year of training experience, participated in the study. Following the 1RM assessment session, participants were randomly assigned to three groups (A, B, and C) according to the protocol proposed by Amiri Khorasani and Gulik (2015) (17). Testing was conducted on three separate days, with at least 48 hours of recovery from heavy activity between sessions. Each evaluation included a general warm-up followed by one of the specific warm-up protocols: ballistic, heavy-resistance, or dynamic stretching of the primary muscles. After completing the assigned warm-up protocol, participants rested for 8 minutes. Subsequently, eight passive reflective markers were attached to anatomical landmarks (lateral tip of the acromion, lateral epicondyle of the elbow, and styloid process of the ulna). In addition, two markers were placed on the barbell, 0.2 m apart (2). Participants then performed a 1RM bench press within the calibrated volume of the 3D motion analysis system. Elbow joint angles and wrist positions were recorded. Barbell balance assessment was conducted as follows. The maximum elbow extension angle at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press was identified. At this angle, the vertical (Z-axis) position of both wrists was determined. The absolute difference between the vertical coordinates of the right and left wrists was calculated and defined as the barbell balance.

3. Results

The angular velocity of elbow extension was also affected across the different events. A significant effect was observed at Vmax1, Vmin, and Vmax2 (F = 8.9, p = 0.013, η² = 0.32). Post hoc comparisons revealed that angular velocity was higher following the ballistic warm-up protocol compared with the dynamic stretching protocol at all events (Fig. 1). In addition, after the ballistic warm-up protocol, a significant improvement in barbell balance was observed compared with the other two protocols (F = 20.2, p = 0.001, η² = 0.44). Specifically, participants demonstrated better balance maintenance and the lowest difference in wrist positions following the ballistic protocol. Although the heavy-resistance warm-up protocol produced better barbell balance compared with the dynamic stretching protocol, the difference was not statistically significant (F = 1.21, p = 0.85, η² = 0.11) (Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of different warm-up protocols—ballistic, heavy-resistance, and dynamic stretching—on barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase of the bench press. The main findings were that elbow extension velocity was higher at Vmax1, Vmin, and Vmax2 following the ballistic warm-up compared with the other two protocols. Furthermore, barbell balance at the end of the concentric phase was significantly better after the ballistic protocol than after either heavy-resistance or dynamic stretching. This enhancement in performance is most likely attributed to post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) (2), which, as suggested by Blazevich and Babault (2019), becomes substantive only after several minutes (21). Several mechanisms may explain the observed improvements in bench press performance following ballistic warm-up. The rapid downward and upward phases of the ballistic bench press may stimulate the stretch-shortening cycle with minimal amortization time between eccentric and concentric actions, thereby maximizing the use of stored elastic energy (22). Additionally, ballistic warm-up may enhance potentiation of contractile elements and increase activation of the pectoral and deltoid muscles, the prime movers in the bench press (4). Another possible mechanism is that during ballistic contractions, the threshold for motor unit recruitment is lower than during slower, ramped contractions (22, 23). These findings provide coaches and athletes, particularly in powerlifting, with a practical and accessible strategy to optimize 1RM bench press performance. Practitioners may consider prescribing ballistic warm-up protocols before maximal bench press attempts.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sport Sciences and Health, University of Tehran (IR.UT.SPORT.REC.1402.136).

Funding

This research did not receive any financial support from the government, private, or non-profit organizations.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this article.

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/06/27 | Accepted: 2025/09/9 | Published: 2025/09/11

Received: 2025/06/27 | Accepted: 2025/09/9 | Published: 2025/09/11

References

1. Rashedi H, Jafarnezhadgero AA, Farokhroo N. The Effect of Ratio of Contraction to Relaxation Durations in PNF Exercises on the Muscle Strength and Range of Motion of Hip Joint. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2015;1(1):45-51.

2. Van Den Tillaar R, Sæterbakken A. The sticking region in three chest-press exercises with increasing degrees of freedom. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2012;26(11):2962-9. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182443430] [PMID]

3. Federation MP. The International Powerlifting Federation. Cell. 1903;90:532-60.

4. Van Den Tillaar R, Ettema G. A comparison of successful and unsuccessful attempts in maximal bench pressing. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2009;41(11):2056-63. [DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a8c360] [PMID]

5. Moir GL, Munford SN, Moroski LL, Davis SE. The effects of ballistic and nonballistic bench press on mechanical variables. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2018;32(12):3333-9. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001835] [PMID]

6. De Freitas MC, Rossi FE, Colognesi LA, De Oliveira JVN, Zanchi NE, Lira FS, et al. Postactivation potentiation improves acute resistance exercise performance and muscular force in trained men. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021;35(5):1357-63. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002897] [PMID]

7. Tillin NA, Bishop D. Factors modulating post-activation potentiation and its effect on performance of subsequent explosive activities. Sports medicine. 2009;39:147-66. [DOI:10.2165/00007256-200939020-00004] [PMID]

8. Hodgson M, Docherty D, Robbins D. Post-activation potentiation: underlying physiology and implications for motor performance. Sports medicine. 2005;35:585-95. [DOI:10.2165/00007256-200535070-00004] [PMID]

9. Xeni J, Gittings WB, Caterini D, Huang J, Houston ME, Grange RW, Vandenboom R. Myosin light-chain phosphorylation and potentiation of dynamic function in mouse fast muscle. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology. 2011;462:349-58. [DOI:10.1007/s00424-011-0965-y] [PMID]

10. McGowan CJ, Pyne DB, Thompson KG, Rattray B. Warm-up strategies for sport and exercise: mechanisms and applications. Sports medicine. 2015;45:1523-46. [DOI:10.1007/s40279-015-0376-x] [PMID]

11. Almasi J, Shabazbigian MM. The Effect of Six Weeks of High-Intensity Interval Training with and without Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Bench Press and Squat Strength in Competitive Male Bodybuilders. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2025;11(1):80-92. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.11.1.80]

12. Zhang Q, Gassier R, Eymard N, Pommel F, Berthier P, Rahmani A, Hautier CA. Predicting Throwing Performance with Force-Velocity Mechanical Properties of the Upper Limb in Experienced Handball Players. J Hum Kinet. 2024;95:43-53. [DOI:10.5114/jhk/190224]

13. Lake J, Lauder M, Smith N, Shorter K. A comparison of ballistic and nonballistic lower-body resistance exercise and the methods used to identify their positive lifting phases. Journal of applied biomechanics. 2012;28(4):431-7. [DOI:10.1123/jab.28.4.431] [PMID]

14. Mausehund L, Krosshaug T. Understanding Bench Press Biomechanics-Training Expertise and Sex Affect Lifting Technique and Net Joint Moments. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2023;37(1):9-17. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004191] [PMID]

15. Ulrich G, Parstorfer M. Effects of plyometric versus concentric and eccentric conditioning contractions on upper-body postactivation potentiation. International journal of sports physiology and performance. 2017;12(6):736-41. [DOI:10.1123/ijspp.2016-0278] [PMID]

16. Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Filip A, Zmijewski P, Zajac A, Tufano JJ. Can post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) improve resistance training volume during the bench press exercise? International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(7):2554. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17072554] [PMID]

17. Amiri-Khorasani M, Gulick DT. Acute effects of different stretching methods on static and dynamic balance in female football players. International journal of therapy and rehabilitation. 2015;22(2):68-73. [DOI:10.12968/ijtr.2015.22.2.68]

18. Sakamoto A, Kuroda A, Sinclair PJ, Naito H, Sakuma K. The effectiveness of bench press training with or without throws on strength and shot put distance of competitive university athletes. European journal of applied physiology. 2018;118:1821-30. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-018-3917-9] [PMID]

19. Bodden D, Suchomel TJ, Lates A, Anagnost N, Moran MF, Taber CB. Acute effects of ballistic and non-ballistic bench press on plyometric push-up performance. Sports. 2019;7(2):47. [DOI:10.3390/sports7020047] [PMID]

20. Garbisu-Hualde A, Gutierrez L, Santos-Concejero J. Post-activation performance enhancement as a strategy to improve bench press performance to volitional failure. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2023;88:199. [DOI:10.5114/jhk/162958] [PMID]

21. Blazevich AJ, Babault N. Post-activation potentiation versus post-activation performance enhancement in humans: historical perspective, underlying mechanisms, and current issues. Frontiers in physiology. 2019;10:1359. [DOI:10.3389/fphys.2019.01359] [PMID]

22. Galay V, Poonia R, Singh M. Understanding the significance of plyometric training in enhancement of sports performance: a systematic review. Vidyabharati International Interdisciplinary Research Journal. 2021;11(2):141-8.

23. Van Cutsem M, Duchateau J, Hainaut K. Changes in single motor unit behaviour contribute to the increase in contraction speed after dynamic training in humans. The Journal of physiology. 1998;513(1):295-305. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.295by.x] [PMID]

24. Ivanova T, Garland S, Miller K. Motor unit recruitment and discharge behavior in movements and isometric contractions. Muscle & Nerve: Official Journal of the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. 1997;20(7):867-74. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199707)20:73.0.CO;2-P]

25. Duchateau J, Hainaut K. Mechanisms of muscle and motor unit adaptation to explosive power training. Strength and power in sport. 2003:316-30. [DOI:10.1002/9780470757215.ch16] [PMID]

26. Linnamo V, Häkkinen K, Komi P. Neuromuscular fatigue and recovery in maximal compared to explosive strength loading. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology. 1997;77:176-81. [DOI:10.1007/s004210050317] [PMID]

27. Raastad T, Hallén J. Recovery of skeletal muscle contractility after high-and moderate-intensity strength exercise. European journal of applied physiology. 2000;82:206-14. [DOI:10.1007/s004210050661] [PMID]

28. Fletcher IM. The effect of different dynamic stretch velocities on jump performance. European journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:491-8. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-010-1386-x] [PMID]

29. Kurak K, İlbak İ, Stojanović S, Bayer R, Purenović-Ivanović T, Pałka T, et al. The Effects of Different Stretching Techniques Used in Warm-Up on the Triggering of Post-Activation Performance Enhancement in Soccer Players. Applied Sciences. 2024;14(11):4347. [DOI:10.3390/app14114347]

30. Judge LW, Avedesian JM, Bellar DM, Hoover DL, Craig BW, Langley J, et al. Pre-and post-activity stretching practices of collegiate soccer coaches in the United State. International journal of exercise science. 2020;13(6):260. [DOI:10.70252/PDCB3344]

31. Gil MH, Neiva HP, Sousa AC, Marques MC, Marinho DA. Current approaches on warming up for sports performance: A critical review. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2019;41(4):70-9. [DOI:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000454]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |