BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-427-en.html

, Monica Chhabra2

, Monica Chhabra2

, Prabhat Kumar3

, Prabhat Kumar3

, Daffylabeth Mawlieh4

, Daffylabeth Mawlieh4

, Nabeel Ahmad5

, Nabeel Ahmad5

, Nitin Sahai *1

, Nitin Sahai *1

2- Department of Physiotherapy, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh-160012, India.

3- Doctoral School of Basic Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary.

4- Assam Down Town University, Guwahati, Assam, India.

5- Department of Biotechnology, School of Allied Sciences, Dev Bhoomi Uttarakhand University—248007, Dehradun, India.

1. Introduction

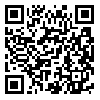

Knee pain is a prevalent musculoskeletal complaint affecting individuals across all age groups, often resulting from complex interactions between proximal, local and distal biomechanical factors (1). The proper management of knee pain depends upon its underlying etiology (2). The foot and ankle, while often overlooked in favour of larger joints like the knee and hip, play a crucial role in human biomechanics. Serving as our primary point of contact with the ground, the foot and ankle are responsible for supporting the weight of the body, absorbing shock, and facilitating various movements, example running, jumping, and walking. Ligaments around the ankle joint, such as the deltoid ligament and the anterior talofibular ligament, provide stability. Meanwhile, tendons like the Achilles tendon, connecting the calf muscles to the calcaneus, play a pivotal role in movement and propulsion (3). As the main point of contact between the body and the ground, the foot has a significant impact on the lower limb's overall biomechanics. The stresses delivered to the knee can be greatly influenced by the complex form and function of the foot. Numerous investigations have examined this issue, highlighting the link between knee pain and foot biomechanics. As the foot adjusts to the ground and absorbs shock, pronation is a typical aspect of the gait cycle. On the other hand, internal rotation of the tibia due to excessive pronation (Fig. 1) can result in malalignment and greater strain on the knee joint (4). Flatfoot, or pes planus, where there is an absence or reduction of the medial arch, can lead to overpronation, and, as mentioned, this can influence the alignment and forces at the knee joint (5).

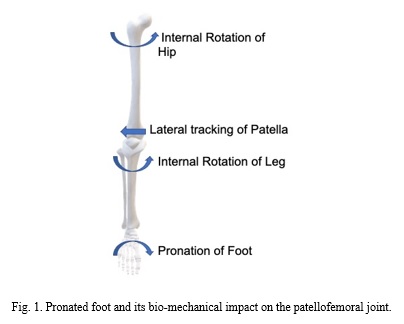

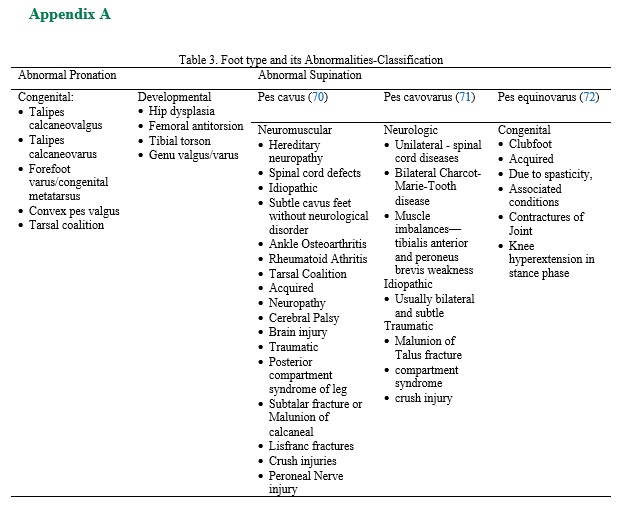

High Arches or Pes Cavus feet with high arches tend to underpronate (or supinate), causing the foot to be less effective at shock absorption. This can transmit increased forces to the knee, especially during high-impact activities, potentially leading to conditions like patellofemoral pain syndrome (6). The type and fit of footwear can influence foot and ankle biomechanics. Poorly fitted or unsupportive shoes might exacerbate abnormal foot biomechanics, leading to altered knee kinetics and kinematics. Elevated heels, for instance, can anteriorly tilt the pelvis, increasing knee flexion (7). Foot biomechanics plays a significant role in knee health. There may be alterations in knee biomechanics as a result of abnormalities or deviations in the anatomy or function of the foot, often resulting in pain or injury. Recognising the role of the foot can guide interventions and preventive strategies in managing knee pain. While appearing uniform in general structure, the human foot can exhibit a wide array of shapes and abnormalities. Such variations often arise from genetic factors, wear and tear, injuries, or even the choice of footwear. Understanding the different foot types and potential abnormalities is vital, as they can significantly influence gait, postural stability, and predisposition to musculoskeletal issues. When an individual with a standard foot type stands or walks, the foot pronates correctly to absorb shock and pressure, which is distributed fairly evenly throughout the foot (8). The different types of abnormal foot conditions have different impacts on gait and knee joint mechanics (Table 1). The classifications of other congenital and developmental foot conditions are attached as Appendix A.

There is minimal study on the epidemiology of knee pain concerning biomechanical origin and its risk factors. In most previous studies, the radiographical evaluation of osteoarthritis (OA) is considered a standard outcome, which may be due to the advantageous objective definition of OA. Few prospective studies have been conducted to determine the risk factors for knee pain, especially in the context of occupational physical loading and physical exercises. As compared to men, women are at a higher risk of developing knee pain (14), especially people with lower educational levels (15). Some studies show that the frequency of knee pain is higher in blue-collar than white-collar workers (16), whereas other studies contradict the same (17). In the comparison of knee pain between the two groups, the first group showed a higher incidence of knee pain. A BMI higher than 26 kg/m², as well as being a present or ex-smoker, was associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing knee pain. Those with a history of knee trauma were almost three times more likely to develop knee pain than those with no history of knee injury (18).

The ankle joint is frequently modelled as a rigid segment in gait analysis, though it permits dorsiflexion and plantar flexion due to morphological constraints of the talocrural joint. For the uniform movement of the center of mass of the body across space, the ankle, subtalar, tarsal, metatarsal, and phalangeal joints have a significant contribution, as these joints constantly make adjustments to different terrain and the actions of the muscles that cross them to provide proper interaction between the body and types of weight-bearing surfaces during locomotion. Thus, the loss of the normal range of motion at these joints has an impact on normal gait and other joints of the entire lower limb (19).

The leg muscles' postural reflexes will change, depending on the surfaces on which the patient is performing locomotion, due to changes in the pressure on the plantar aspect (20). Foot orthoses are used to preserve rotational equilibrium and correct the subtalar joint axis (21), as per sagittal plane facilitation theory (22).

Considering the malalignment and shift in weight distribution due to foot and ankle deformity, it might have an effect like malalignment and muscle imbalance, leading to functional impairment and pain in proximal joints, e.g., knee, hip, and spine. For example, knee pain may worsen if the medial longitudinal arch is collapsed. Lowering the medial longitudinal arch may cause the knee joint to become malaligned, changing the knee joint's biomechanics and intensifying knee pain (23). In the relationship between the asymptomatic foot and knee pain, it is observed that knee pain has a high prevalence of PF joint involvement as compared to the tibiofemoral joint, with aggravating factors such as squatting, ascending, descending, and running, which is summarized below. Multiple studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between foot mechanics, particularly pronated foot posture, rearfoot eversion, and midfoot mobility, and the onset or aggravation of PFP (24). Common pain-inducing activities include squatting, stair ascent/descent, kneeling, and prolonged sitting (25).

The key biomechanical factors influencing PFP are, rearfoot range of motion (ROM) during dynamic tasks (e.g., stair climbing) showed the strongest predictive value (26), increased knee flexion angles and external loads during squats elevate Patello-Femoral (PF) joint stress (27), individuals with flat feet or altered foot progression angles often exhibit malalignment or increased joint loading, though some studies reported inconsistent loading responses (28), static foot posture had less impact on knee joint mechanics in asymptomatic individuals (29), chronic PFP is associated with poorer prognosis and is more prevalent in those with greater navicular drop and pronated feet (30), medial foot loading may reduce medial knee stress, while lateral loading increases it, which is contraindicated in medial knee osteoarthritis (OA) (31).

Based on extensive studies on different types of knee pain and compartments involved, the patellofemoral joint (PFJ) has a high prevalence of developing osteoarthritis as compared to the tibiofemoral compartment, studied under the high radiographic and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) evidence (32), and knee osteoarthritis is a sequela of knee pain due to repetitive overloading associated with joint cartilage degeneration (33). Whereas, studies underscore the critical role of modifiable foot mechanics in preventing and managing knee pain, especially PFP.

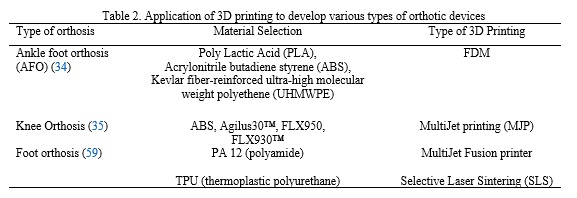

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a potential orthopaedic and rehabilitation technique in recent years. Its applications span from the production of patient-specific anatomical models for pre-surgical planning to the fabrication of personalized orthoses and prosthetic devices that optimize joint alignment and reduce knee loading (34). 3D-printed braces and insoles have demonstrated promise in treating knee pain by improving gait biomechanics, improving patient comfort, and offering customized mechanical support. Additionally, 3D printing allows for quick prototyping and affordable customisation, providing a non-pharmacological treatment option to supplement traditional treatments for musculoskeletal conditions (35). This review study attempts to objectively assess the effectiveness of non-pharmacological therapies and integrate current knowledge on distal biomechanical contributions to knee pain with the growing significance of 3D printing in customized rehabilitation strategies.

2. Methods

Knee pain is a complex condition frequently influenced by distal factors such as lower limb posture, foot morphology, and overall biomechanics. These interrelated factors alter the distribution of loads across the knee joint and may contribute to the onset or persistence of pain. Because non-pharmacological approaches—particularly orthotic interventions enhanced by emerging technologies like 3D printing—are gaining clinical importance, it is essential to consolidate current research in this domain. Therefore, the purpose of this narrative review was to summarize contemporary management strategies, with a special focus on 3D printing applications, and to provide an updated overview of distal biomechanical influences on knee pain.

2.1 Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar for studies published up to August 21, 2025. Both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords were used, including foot biomechanics, distal structures, orthotics, 3D printing, knee pain, patellofemoral pain, knee osteoarthritis, and non-pharmacological therapy. Boolean operators (“AND,” “OR”) were applied to refine the search. Initially, approximately 1,240 records were retrieved. After removing duplicates and irrelevant publications, 980 articles remained. Based on title and abstract screening, 260 papers were deemed potentially relevant. Following full-text evaluation, 77 studies that met the inclusion criteria and were most pertinent to the objectives of this review were selected for synthesis.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria: i. Studies examining how distal factors—such as lower limb alignment, gait mechanics, or foot and ankle morphology—contribute to the development or persistence of knee pain. ii. Studies providing data on non-pharmacological interventions, including 3D-printed orthoses, physiotherapy, footwear modification, and orthotic devices. iii. Original research (randomized controlled trials, cohort, or case–control studies) or high-quality systematic and narrative reviews.

Exclusion Criteria: i. Studies focusing exclusively on pharmacological or surgical treatments. ii. Publications not written in English. iii. Case reports lacking sufficient biomechanical or interventional information.

2.3 Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers screened all titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies. Full texts of eligible papers were then reviewed in detail. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. Extracted data included study design, sample characteristics, assessed distal parameters, intervention type, outcome measures, and principal findings.

2.4 Data Synthesis

Given the qualitative nature of most included studies, a thematic synthesis approach was adopted. Studies were categorized into three major themes: I. The biomechanical and anatomical relationship between knee pain and distal variables. II. The effectiveness of non-pharmacological treatments such as exercise therapy, orthoses, and gait retraining. III. Innovations in orthotic design, including additive manufacturing and 3D printing technologies.

The synthesis aimed to identify consistent patterns, highlight gaps in the literature, and propose directions for future research. Overall, evidence suggests that no single non-pharmacological intervention is universally effective. Instead, multi-modal approaches—combining exercise therapy, weight control, and biomechanical correction—yield superior outcomes compared to isolated treatments. Nonetheless, high-quality, long-term comparative trials are still needed, particularly concerning the integration of 3D-printed orthoses and behavioural interventions into standard clinical care. Future studies should also prioritize protocol standardization, comparative evaluation of treatment combinations, and cost-effectiveness analyses to enhance clinical applicability.

3. Results

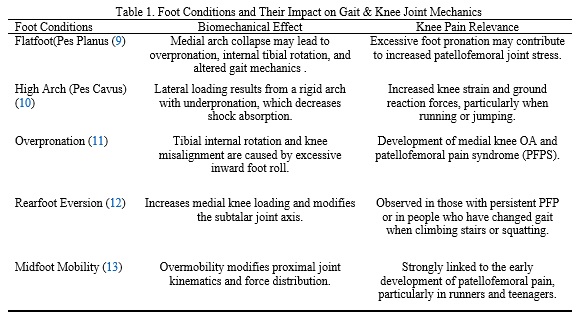

The multifactorial etiology of knee pain highlights the necessity of an integrated, non-pharmacological management approach (Fig. 2). Biomechanical, anatomical, and functional factors all play central roles in its development and persistence. Among these, interventions targeting lower limb biomechanics and foot morphology have demonstrated notable potential in alleviating symptoms and improving functional outcomes. Nevertheless, the evidence regarding their effectiveness remains mixed, with treatment success often influenced by individual patient characteristics, adherence to therapy, and the presence of comorbid conditions.

3.1. Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation

Most studies consistently emphasize exercise-based rehabilitation as the cornerstone of non-surgical management for knee pain (36). Strengthening periarticular muscles, particularly the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles, enhances joint stability and reduces pain (37). Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that resistance training produces superior outcomes compared with passive modalities, reinforcing the consensus that active rehabilitation provides more sustainable, long-term benefits (38). However, the magnitude of improvement varies among studies, often depending on patient adherence, exercise intensity, and program duration (39). Gait retraining and proprioceptive training have also shown significant effectiveness but require individualized adjustment based on patient-specific needs (40–42).

3.2. Lifestyle Modification

Obesity and excess body weight are well-established, modifiable risk factors for both the onset and progression of knee osteoarthritis and knee pain (43). The relationship is twofold: mechanical, due to increased joint loading (44), and biochemical, mediated by inflammatory cytokines released from adipose tissue (45). Numerous studies confirm that weight reduction interventions consistently alleviate pain, enhance mobility, and slow disease progression, although the extent of these benefits varies according to baseline weight and adherence (46–50).

3.3. Orthotic Intervention: Traditional vs 3D-Printed Devices

Evidence regarding orthotic devices remains mixed. While prefabricated orthoses provide short-term symptomatic relief, they often fail to achieve meaningful long-term biomechanical correction (51). In contrast, customized 3D-printed orthoses have demonstrated superior outcomes by improving plantar pressure distribution, gait mechanics, and pain reduction (34, 52–53).

3D printing offers key advantages such as personalized customization, rapid prototyping, and high anatomical precision, making it a transformative technology in orthotic design (54–55). Despite its promise, 3D printing remains cost-intensive and lacks sufficient evidence from large-scale randomized controlled trials (56). Additionally, 3D printing’s strengths—such as fast production cycles, reproducibility, biodegradable adaptive materials, and minimal material waste (Fig. 3)—extend its application beyond orthoses to surgical templates, implants, and anatomical models. The incorporation of composite materials, such as carbon or glass fiber fillers, further enhances the structural strength and flexibility of these devices, tailoring them to specialized orthopedic requirements (57). Details are summarized in Table 2. Studies confirm that customized 3D-printed insoles outperform prefabricated models in both comfort and biomechanical correction, particularly by achieving a more even distribution of plantar loads. Reported adverse effects are minimal, suggesting that these insoles serve as a reliable and well-tolerated adjunct to physiotherapy interventions (58).

3.4. Psychological Factors Influencing Knee Pain and Its Management

By addressing psychological barriers through cognitive-behavioural approaches, patient adherence to rehabilitation programs can be significantly improved. Such interventions help modify maladaptive thoughts and behaviours related to pain, reducing fear-avoidance patterns and enhancing motivation for active participation. The long-term outcomes of these approaches, including improved pain coping and functional recovery, are summarized in Appendix B.

4. Discussion

This review confirms that knee pain arises from a complex interplay of biomechanical, functional, and psychosocial factors, reinforcing the importance of a comprehensive and individualized non-pharmacological management approach. The literature consistently emphasizes that mechanical determinants—especially lower limb alignment and distal biomechanical features such as foot morphology—play pivotal roles in both the development and persistence of knee pain. Recent umbrella reviews and EULAR guideline updates underscore the significance of personalized, multicomponent management strategies as the cornerstone of evidence-based recommendations for knee osteoarthritis (OA) and related conditions (58, 60). These strategies typically incorporate patient-centred exercise programs, weight management, and educational interventions, all of which are shown to effectively alleviate symptoms and improve physical function (61).

Technological advances have notably expanded the scope of orthotic management. The adoption of three-dimensional (3D) printing in orthotic device fabrication has gained increasing attention. Meta-analyses and emerging clinical evidence demonstrate that 3D-printed insoles and braces provide enhanced biomechanical correction, more uniform plantar pressure distribution, and greater comfort than traditional prefabricated models (62). The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into design optimization and material innovation further enables patient-specific customization across various pathologies, marking a major step toward precision rehabilitation (63). Nevertheless, these benefits are tempered by practical challenges, including high production costs, limited scalability, and a paucity of large-scale comparative clinical trials to substantiate long-term outcomes (64).

Lifestyle interventions remain a fundamental pillar of management. Obesity—acknowledged as both a biomechanical and biochemical risk factor—is strongly associated with OA progression through mechanisms involving mechanical overload and adipose-derived inflammatory cytokines. Sustainable weight reduction, particularly when implemented within structured self-management and educational programs, remains a highly supported evidence-based recommendation (60, 65). Rehabilitation approaches are evolving as well. Network meta-analyses suggest modest additional benefits from adjunct therapies such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, and gait retraining. However, the prevailing consensus emphasizes that structured, adherence-driven exercise therapy—especially resistance and proprioceptive training—continues to yield the most consistent long-term outcomes when tailored and supervised by experienced clinicians (58, 60, 65). A major advancement since 2024 has been the growing evidence supporting psychological interventions as integral components of knee pain management. High-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate that cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, and stress management substantially improve pain perception, physical function, and self-efficacy in individuals with knee OA (66, 67). These interventions most notably enhance self-management abilities and chronic pain coping skills, suggesting that they should be formally incorporated into multidisciplinary treatment frameworks. Despite rapid growth in this field, heterogeneity in intervention content, delivery methods, and follow-up duration continues to hinder standardization—highlighting the need for protocol refinement in future research (68).

Persistent limitations across the literature include variability in study populations, differences in intervention intensity and duration, and a general lack of long-term follow-up data. Moreover, the clinical and economic effectiveness of emerging modalities—such as 3D-printed orthoses and digital health tools—remains to be confirmed through large, pragmatic, and cost-effectiveness trials (62, 69). Further investigation is also needed into the influence of modifiable risk factors (e.g., comorbidities, occupational load, physical activity type) and underrepresented populations such as younger adults and patients with multiple comorbidities (60).

5. Conclusion

Knee pain is a multifactorial condition influenced by foot biomechanics, obesity, muscle imbalance, and lower-limb alignment, with age acting as a risk factor due to its association with degenerative changes. It affects not only physical function but also overall well-being. Advances in 3D printing have shown promise in enabling more personalized orthotic solutions tailored to individual anatomy, which may enhance prevention and treatment strategies in select cases. Conservative strategies—such as physical therapy, orthotics, and lifestyle modification—offer effective, holistic management by addressing underlying causes. Emerging technologies like AI, wearables, and 4D printing signal a shift toward proactive, personalized interventions. Patellofemoral pain (PFP), however, remains a diagnostic challenge due to its complex etiology and lack of clear imaging markers. Nonetheless, interdisciplinary approaches integrating orthopedics, biomechanics, and technology promise improved care and outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a narrative review and does not include any studies involving human participants or animals conducted by the authors. All procedures adhered to the ethical standards for research integrity and reporting, as outlined by the Journal of Sports Biomechanics.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualisation, supervision, and review: Dr. Nitin Sahai. Methodology and writing – original draft: J. P. Darjee. Resources: Dr. Monica Chhabra and Prabhat Kumar. Software and visualisation: Daffylabeth Mawlieh. Validation: Dr. Nabeel Ahmed. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this work.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A

Appendix B

Knee Pain Influenced by Psychological Factors and Its Management.

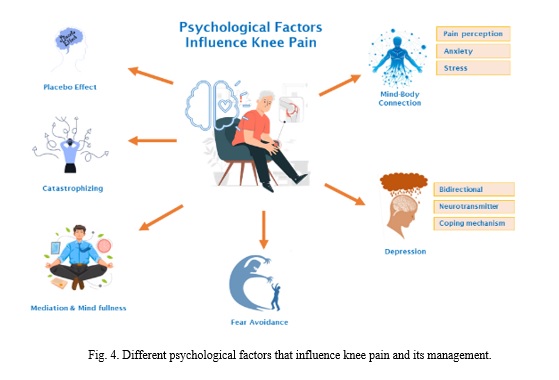

The impact and prevalence of knee pain on individuals across the globe cannot be underestimated. This widespread and incapacitating condition significantly impacts millions of individuals' daily lives (73). The etiology of knee pain is commonly linked to physiological factors such as injury, arthritis, or mechanical issues. However, recent investigations have shed light on the substantial influence exerted by psychological factors in both the onset and management of knee pain (74). This section of the review articles explores the complex relationship of psychological factors that exert influence on the experience of knee pain. It aims to shed light on the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon and provide insights into potential strategies for effectively managing knee pain within a psychological framework. The subsequent information offers a concise overview of the diverse psychological factors shown (Fig. 4) below, which exert a significant influence on the occurrence and management of knee pain.

The Mind-Body Connection: The relationship between the mind and body is of paramount importance in the therapy of knee pain. Psychological variables, such as anxiety, stress, and depression, have the potential to intensify the perception of pain. Conversely, implementing mindfulness practices, relaxation techniques, and positive cognitive processes can mitigate pain. The integration of mental and physical therapies is crucial for achieving comprehensive relief from knee pain (75).

Depression: There is a strong relationship between knee pain and depression. The presence of chronic pain resulting from knee-related conditions has the potential to induce or exacerbate depressive symptoms, mostly attributable to the constrained physical mobility and diminished overall well-being experienced by affected individuals. On the contrary, depression has the potential to amplify the experience of pain and impede the process of healing. It is imperative to priorities individuals' holistic well-being and medical and psychological interventions to effectively address both problems concurrently (76).

Fear Avoidance: According to the fear-avoidance model, individuals experiencing knee pain may develop a fear response towards movement as a result of their anticipation of pain. The presence of this dread has the potential to result in the avoidance of engaging in physical activities, potentially contributing to a state of deconditioning. Ultimately, this deconditioning can worsen the experience of knee pain (77).

The experience of knee pain extends beyond its physical manifestation, encompassing a multifaceted interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. A comprehensive comprehension of the psychological aspects associated with knee pain and their subsequent influence is essential to facilitate the implementation of effective pain management strategies. Through the examination of stress, anxiety, depression, fear avoidance, social support, pain beliefs, and attitudes, this study aims to explore the potential benefits of incorporating mind-body changes into the management of knee pain. By adopting a more comprehensive and holistic approach, healthcare professionals involved in knee pain management may be able to provide a more effective and well-rounded therapeutic experience for individuals suffering from knee pain.

Received: 2025/08/20 | Accepted: 2025/11/6 | Published: 2025/11/12

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |