Volume 12, Issue 2 (9-2026)

J Sport Biomech 2026, 12(2): 224-241 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghadimi kalateh Z, Sheikh M, Qeysari S F, Hoomanian D, Bagherzadeh F. The Effect of Equine-Assisted Therapy and Play Therapy on Gross Perceptual-Motor Performance and Related Biomechanical Parameters in Adolescents with Autism. J Sport Biomech 2026; 12 (2) :224-241

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-459-en.html

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-459-en.html

Zahra Ghadimi kalateh1

, Mahmoud Sheikh *2

, Mahmoud Sheikh *2

, Seyyed Fardin Qeysari1

, Seyyed Fardin Qeysari1

, Davood Hoomanian1

, Davood Hoomanian1

, Fazlollah Bagherzadeh1

, Fazlollah Bagherzadeh1

, Mahmoud Sheikh *2

, Mahmoud Sheikh *2

, Seyyed Fardin Qeysari1

, Seyyed Fardin Qeysari1

, Davood Hoomanian1

, Davood Hoomanian1

, Fazlollah Bagherzadeh1

, Fazlollah Bagherzadeh1

1- Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Play therapy, Equine-assisted therapy, Perceptual-motor skills, Movement biomechanics, Autism

Full-Text [PDF 1920 kb]

(102 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (328 Views)

Full-Text: (155 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors (1). Beyond these core diagnostic features, children and adolescents with ASD commonly experience impairments in both fine and gross motor skills, including balance, coordination, strength, and motor planning (2). Such motor difficulties can hinder daily functioning, limit participation in physical and social activities, and negatively affect overall developmental outcomes. Because motor control challenges often emerge early and persist over time, understanding their underlying mechanisms and implementing targeted interventions from childhood onward is essential (3). A growing body of research supports the effectiveness of movement-based interventions for improving motor and functional abilities in individuals with ASD. Systematic reviews indicate that physical activity programs, aquatic therapy, structured exercise, and equine-assisted approaches can enhance participation, motor function, body structure, and activity levels (4). Exercise-based programs have also been associated with reductions in stereotyped behaviors and improvements in emotional regulation, social interaction, cognitive performance, and attention (5).

Perceptual-motor skills form the foundation for higher-level motor learning and should therefore be emphasized during early stages of development (6). These abilities contribute to cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor growth and are essential for successful movement execution across daily and sport-related tasks (7). However, children with ASD often struggle with perceptual-motor demands required for routine activities (8). Despite their importance, perceptual-motor delays—driven by multisensory and neuromotor processing challenges—have received less attention than social deficits, highlighting the need for comprehensive assessment and intervention (9). Equine-assisted therapy (EAT) is an integrative therapeutic modality that uses the rhythmic, three-dimensional movement of the horse to stimulate postural control, muscle tone regulation, and balance (10). Evidence suggests that EAT produces meaningful improvements in social, behavioral, and motor outcomes in individuals with ASD (11–13). Play therapy, another widely used intervention, promotes cognitive, social, emotional, and motor development (14,15). Studies show that play-based programs can improve gross motor skills, reduce maladaptive behaviors, and enhance coordination and agility in children with ASD (16–18,22).

Despite substantial evidence for each approach independently, no prior study has directly compared the effects of EAT and structured play therapy on gross perceptual-motor skills and related biomechanical parameters in adolescents with ASD. Given the central role of motor abilities such as balance, bilateral coordination, strength, and agility in functional independence and daily movement (20,21), comparative research is needed to guide evidence-based intervention selection. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine and compare the effects of equine-assisted therapy and play therapy on perceptual-motor performance and associated biomechanical parameters in adolescents with ASD.

2. Methods

This semi-experimental study employed a pre-test–post-test design with a control group to evaluate intervention effects. A total of 36 adolescents with ASD (25 boys, 11 girls), aged 10 to 14 years, were recruited through convenience sampling from local centers and clinics. Participants were carefully matched based on age, gender, and severity of ASD symptoms, and then randomly assigned to one of three groups: equine-assisted therapy (n = 12), play therapy (n = 12), or control (n = 12). Interventions lasted eight weeks, with five 30-minute sessions per week, and were tailored to accommodate the individual abilities of each participant. The control group continued with their usual activities and center programs. Gross perceptual-motor skills were assessed using the Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP), including subtests for running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, and muscle strength, one day before and one day after the intervention period. Data were analyzed using paired-sample t-tests, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and Bonferroni post-hoc tests to examine group differences.

3. Results

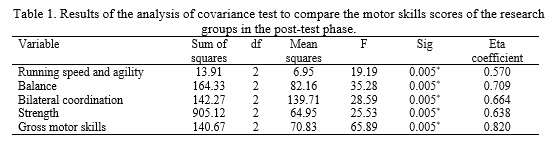

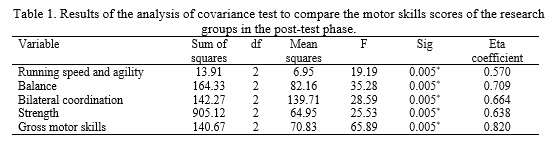

The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that all variables were normally distributed across the three groups (p > 0.05). Paired-sample t-tests showed significant improvements in overall gross motor skills from pretest to posttest in both the equine-assisted therapy (t(11) = -19.549, p < 0.001) and play therapy groups (t(11) = -19.082, p < 0.005), while the control group showed no significant change (t(11) = 1.617, p = 0.137). Subtest analyses revealed significant gains in running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, and strength in both intervention groups, with no improvements in the control group. ANCOVA confirmed significant between-group differences in posttest scores (Table 1), and Bonferroni tests indicated that the control group scored lower than both intervention groups (p ≤ 0.005).

The equine-assisted therapy group outperformed the play therapy group in overall gross motor skills (p = 0.01), running speed and agility (p = 0.02), balance (p = 0.005), and strength (p = 0.07), but no difference was found in bilateral coordination (p = 0.476). These findings demonstrate that both interventions effectively improve gross motor skills in adolescents with ASD, with equine-assisted therapy providing greater benefits across most subdomains.

1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors (1). Beyond these core diagnostic features, children and adolescents with ASD commonly experience impairments in both fine and gross motor skills, including balance, coordination, strength, and motor planning (2). Such motor difficulties can hinder daily functioning, limit participation in physical and social activities, and negatively affect overall developmental outcomes. Because motor control challenges often emerge early and persist over time, understanding their underlying mechanisms and implementing targeted interventions from childhood onward is essential (3). A growing body of research supports the effectiveness of movement-based interventions for improving motor and functional abilities in individuals with ASD. Systematic reviews indicate that physical activity programs, aquatic therapy, structured exercise, and equine-assisted approaches can enhance participation, motor function, body structure, and activity levels (4). Exercise-based programs have also been associated with reductions in stereotyped behaviors and improvements in emotional regulation, social interaction, cognitive performance, and attention (5).

Perceptual-motor skills form the foundation for higher-level motor learning and should therefore be emphasized during early stages of development (6). These abilities contribute to cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor growth and are essential for successful movement execution across daily and sport-related tasks (7). However, children with ASD often struggle with perceptual-motor demands required for routine activities (8). Despite their importance, perceptual-motor delays—driven by multisensory and neuromotor processing challenges—have received less attention than social deficits, highlighting the need for comprehensive assessment and intervention (9). Equine-assisted therapy (EAT) is an integrative therapeutic modality that uses the rhythmic, three-dimensional movement of the horse to stimulate postural control, muscle tone regulation, and balance (10). Evidence suggests that EAT produces meaningful improvements in social, behavioral, and motor outcomes in individuals with ASD (11–13). Play therapy, another widely used intervention, promotes cognitive, social, emotional, and motor development (14,15). Studies show that play-based programs can improve gross motor skills, reduce maladaptive behaviors, and enhance coordination and agility in children with ASD (16–18,22).

Despite substantial evidence for each approach independently, no prior study has directly compared the effects of EAT and structured play therapy on gross perceptual-motor skills and related biomechanical parameters in adolescents with ASD. Given the central role of motor abilities such as balance, bilateral coordination, strength, and agility in functional independence and daily movement (20,21), comparative research is needed to guide evidence-based intervention selection. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine and compare the effects of equine-assisted therapy and play therapy on perceptual-motor performance and associated biomechanical parameters in adolescents with ASD.

2. Methods

This semi-experimental study employed a pre-test–post-test design with a control group to evaluate intervention effects. A total of 36 adolescents with ASD (25 boys, 11 girls), aged 10 to 14 years, were recruited through convenience sampling from local centers and clinics. Participants were carefully matched based on age, gender, and severity of ASD symptoms, and then randomly assigned to one of three groups: equine-assisted therapy (n = 12), play therapy (n = 12), or control (n = 12). Interventions lasted eight weeks, with five 30-minute sessions per week, and were tailored to accommodate the individual abilities of each participant. The control group continued with their usual activities and center programs. Gross perceptual-motor skills were assessed using the Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP), including subtests for running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, and muscle strength, one day before and one day after the intervention period. Data were analyzed using paired-sample t-tests, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and Bonferroni post-hoc tests to examine group differences.

3. Results

The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that all variables were normally distributed across the three groups (p > 0.05). Paired-sample t-tests showed significant improvements in overall gross motor skills from pretest to posttest in both the equine-assisted therapy (t(11) = -19.549, p < 0.001) and play therapy groups (t(11) = -19.082, p < 0.005), while the control group showed no significant change (t(11) = 1.617, p = 0.137). Subtest analyses revealed significant gains in running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, and strength in both intervention groups, with no improvements in the control group. ANCOVA confirmed significant between-group differences in posttest scores (Table 1), and Bonferroni tests indicated that the control group scored lower than both intervention groups (p ≤ 0.005).

The equine-assisted therapy group outperformed the play therapy group in overall gross motor skills (p = 0.01), running speed and agility (p = 0.02), balance (p = 0.005), and strength (p = 0.07), but no difference was found in bilateral coordination (p = 0.476). These findings demonstrate that both interventions effectively improve gross motor skills in adolescents with ASD, with equine-assisted therapy providing greater benefits across most subdomains.

4. Discussion

The present study examined and compared the effects of equine-assisted therapy (EAT) and structured play therapy on gross perceptual–motor skills and related biomechanical parameters—including running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, and strength—in adolescents with ASD. Both interventions produced significant improvements across all gross motor domains relative to the control group, and the EAT group demonstrated superior gains in most biomechanical parameters, although no significant difference emerged for bilateral coordination. These findings reinforce the potential of EAT as a complementary motor-based intervention for ASD. The rhythmic, multidirectional movement of the horse closely mimics human gait and continuously challenges postural control, thereby promoting improvements in balance, neuromuscular activation, and overall gross motor performance (11). Sensory integration, tonic–postural regulation, and enhanced visual–motor coordination may further contribute to these benefits (27,28). Consistent with previous evidence, EAT has also been associated with reductions in stereotyped behaviors and improvements in self-regulation, arousal, and motor functioning (29,30).

Play therapy likewise led to meaningful gains in gross motor skills. Adolescents with ASD often face reduced opportunities for physical play and structured exercise due to social communication challenges, motor planning difficulties, and environmental barriers (31,32). Play-based interventions provide guided, repetitive, and goal-oriented motor experiences that can improve coordination, balance, and movement organization (33,34). These benefits align with prior research demonstrating improved agility, bilateral coordination, and gross motor performance following structured play programs (18,22). Although both interventions were effective, the relatively greater improvements in the EAT group may be partially explained by the unique behavioral profile of adolescents with ASD. Communication challenges may hinder responsiveness to human-mediated interactions in play therapy, whereas the nonverbal, lower-demand nature of human–horse interaction may facilitate engagement, reduce anxiety, and enhance motivation (35). Social motivation and social–cognitive theories also suggest that observing and responding to an animal’s behavior may strengthen attention, participation, and treatment adherence (13,36).

Both EAT and play therapy substantially improved perceptual–motor performance and biomechanical parameters in adolescents with ASD, with EAT demonstrating somewhat stronger effects in several domains. However, differences between groups should be interpreted cautiously, given that small changes in BOTMP raw scores may result in notable shifts in scaled scores. Limitations—including sample specificity, lack of long-term follow-up, reliance on BOTMP, and uncontrolled environmental factors—should guide future research toward more comprehensive and generalizable designs.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sports Science Research Institute under the code IR.SSRC.REC.1400.001.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

The present study examined and compared the effects of equine-assisted therapy (EAT) and structured play therapy on gross perceptual–motor skills and related biomechanical parameters—including running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, and strength—in adolescents with ASD. Both interventions produced significant improvements across all gross motor domains relative to the control group, and the EAT group demonstrated superior gains in most biomechanical parameters, although no significant difference emerged for bilateral coordination. These findings reinforce the potential of EAT as a complementary motor-based intervention for ASD. The rhythmic, multidirectional movement of the horse closely mimics human gait and continuously challenges postural control, thereby promoting improvements in balance, neuromuscular activation, and overall gross motor performance (11). Sensory integration, tonic–postural regulation, and enhanced visual–motor coordination may further contribute to these benefits (27,28). Consistent with previous evidence, EAT has also been associated with reductions in stereotyped behaviors and improvements in self-regulation, arousal, and motor functioning (29,30).

Play therapy likewise led to meaningful gains in gross motor skills. Adolescents with ASD often face reduced opportunities for physical play and structured exercise due to social communication challenges, motor planning difficulties, and environmental barriers (31,32). Play-based interventions provide guided, repetitive, and goal-oriented motor experiences that can improve coordination, balance, and movement organization (33,34). These benefits align with prior research demonstrating improved agility, bilateral coordination, and gross motor performance following structured play programs (18,22). Although both interventions were effective, the relatively greater improvements in the EAT group may be partially explained by the unique behavioral profile of adolescents with ASD. Communication challenges may hinder responsiveness to human-mediated interactions in play therapy, whereas the nonverbal, lower-demand nature of human–horse interaction may facilitate engagement, reduce anxiety, and enhance motivation (35). Social motivation and social–cognitive theories also suggest that observing and responding to an animal’s behavior may strengthen attention, participation, and treatment adherence (13,36).

Both EAT and play therapy substantially improved perceptual–motor performance and biomechanical parameters in adolescents with ASD, with EAT demonstrating somewhat stronger effects in several domains. However, differences between groups should be interpreted cautiously, given that small changes in BOTMP raw scores may result in notable shifts in scaled scores. Limitations—including sample specificity, lack of long-term follow-up, reliance on BOTMP, and uncontrolled environmental factors—should guide future research toward more comprehensive and generalizable designs.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sports Science Research Institute under the code IR.SSRC.REC.1400.001.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/11/11 | Accepted: 2025/12/11 | Published: 2025/12/13

Received: 2025/11/11 | Accepted: 2025/12/11 | Published: 2025/12/13

References

1. Lord C, Brugha TS, Charman T, Cusack J, Dumas G, Frazier T, et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2020;6(1):1-23. [DOI:10.1038/s41572-019-0138-4] [PMID]

2. Kangarani-Farahani M, Malik MA, Zwicker JG. Motor impairments in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2024;54(5):1977-97. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-023-05948-1] [PMID]

3. Henderson H, Fuller A, Noren S, Stout VM, Williams D. The effects of a physical education program on the motor skill performance of children with autism spectrum disorder. Palaestra. 2016;30(3):322-34.

4. Ruggeri A, Dancel A, Johnson R, Sargent B. The effect of motor and physical activity intervention on motor outcomes of children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Autism. 2020;24(3):544-68. [DOI:10.1177/1362361319885215] [PMID]

5. Bremer E, Crozier M, Lloyd M. A systematic review of the behavioural outcomes following exercise interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20(8):899-915. [DOI:10.1177/1362361315616002] [PMID]

6. Fatahi A, Panjehzadeh B, Koreli Z, Zehtab Asghari H. Comparison of motor skills and postures of elite male teenage volleyball and basketball players. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2021;6(4):226-39. [DOI:10.32598/biomechanics.6.3.2]

7. Butterfield SA, Lehnhard RA, Coladarci T. Age, sex, and body mass index in performance of selected locomotor and fitness tasks by children in grades K-2. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2002;94(1):80-6. [DOI:10.2466/pms.2002.94.1.80] [PMID]

8. Minoei A, Sheikh M, Hemayattalab R, Olfatian U. Examining horse therapy in 8-12-year-old boys with autism spectrum disorder. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences. 2015;9(5):761-5.

9. Linkenauger SA, Lerner MD, Ramenzoni VC, Proffitt DR. A perceptual-motor deficit predicts social and communicative impairments in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research. 2012;5(5):352-62. [DOI:10.1002/aur.1248] [PMID]

10. Stergiou A, Tzoufi M, Ntzani E, Varvarousis D, Beris A, Ploumis A. Therapeutic effects of horseback riding interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2017;96(10):717-25. [DOI:10.1097/PHM.0000000000000726] [PMID]

11. Dawson S, McCormick BP, Tamas D, Stanojevic C, Eldridge L, McIntire J, et al. Equine-assisted therapy with autism spectrum disorder in Serbia and the United States. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2022;56(1):17-38. [DOI:10.18666/TRJ-2022-V56-I1-10387]

12. Zoccante L, Marconi M, Ciceri ML, Gagliardoni S, Gozzi LA, Sabaini S, et al. Effectiveness of equine-assisted activities and therapies for improving adaptive behavior and motor function in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(8):1726-39. [DOI:10.3390/jcm10081726] [PMID]

13. Zenenga A, Phillips J, Nyashanu M, Ekpenyong MS. Exploring the impact of animal involvement in the learning experiences of learners mainly with autism in the English West Midlands region: a qualitative study. Journal of Education. 2023;203(1):10-17. [DOI:10.1177/0022057420987497]

14. Case L, Joonkoo Y. The effect of different intervention approaches on gross motor outcomes of children with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2019;36(4):501-26. [DOI:10.1123/apaq.2018-0174] [PMID]

15. Taylor L, Ray DC. Child-centered play therapy and social-emotional competencies of African American children: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2021;30(2):74-86. [DOI:10.1037/pla0000152]

16. Brefort E, Saint-Georges-Chaumet Y, Cohen D, Saint-Georges C. Two-year follow-up of 90 children with autism spectrum disorder receiving intensive developmental play therapy (3i method). BMC Pediatrics. 2022;22(1):1-13. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-022-03431-x] [PMID]

17. Phytanza DTP, Burhaein E. Aquatic activities as play therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disabilities Sports and Health Sciences. 2019;2(2):64-71. [DOI:10.33438/ijdshs.652086]

18. Hassani F, Shahrbanian S, Shahidi SH, Sheikh M. Playing games can improve physical performance in children with autism. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2022;68(2):219-26. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2020.1752995] [PMID]

19. Hossein Khanzadeh AA, Imankhah F. The effect of music therapy along with play therapy on social behaviors and stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. Practice in Clinical Psychology. 2017;5(4):251-62. [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.251]

20. Vives-Vilarroig J, Ruiz-Bernardo P, García-Gómez A. Effects of horseback riding on the postural control of autistic children: a multiple baseline across-subjects design. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2025;55(2):510-23. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-023-06174-5] [PMID]

21. Meera B, Fields B, Healy S, Columna L. Equine-assisted services for motor outcomes of autistic children: a systematic review. Autism. 2024;28(12):3002-14. [DOI:10.1177/13623613241255294] [PMID]

22. Mohammadzadeh S, Habibifar F, Ramezanzade H, Jafarzadeh M, Rabavi A, Kurnaz M, et al. The effect of a play-centered SPARK physical education program on motor proficiency and self-efficacy in children with developmental coordination disorder. Sport Sciences for Health. 2025;21(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1007/s11332-025-01385-y]

23. Wilson BN, Kaplan BJ, Crawford SG, Dewey D. Interrater reliability of the Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency-long form. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2000;17(1):95-110. [DOI:10.1123/apaq.17.1.95]

24. Borgi M, Loliva D, Cerino S, Chiarotti F, Venerosi A, Bramini M, et al. Effectiveness of a standardized equine-assisted therapy program for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-015-2530-6] [PMID]

25. Schottelkorb AA, Swan KL, Ogawa Y. Intensive child-centered play therapy for children on the autism spectrum: a pilot study. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2020;98(1):63-73. [DOI:10.1002/jcad.12300]

26. Faramarzi H, Ghanei M. The effectiveness of play therapy based on cognitive-behavioral therapy on challenging behaviors of high-functioning autistic children. Psychology of Exceptional Individuals. 2020;9(36):169-85.

27. Kyvelidou A, Godden E, Otte K, Smith K, Peck K, Adamiec M, et al. Effectiveness of a 6-week occupational therapy program with hippotherapy on postural control and social behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2024;5(14):1-13. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2024.2363023]

28. Aldridge RL, Morgan A, Lewis A. The effects of hippotherapy on motor performance in veterans with disabilities: a case report. Journal of Military and Veterans Health. 2016;24(3):24-7.

29. Cotor G, Cotor DC, Zagrai G, Grama A, Cupșa E, Damian A. The impact of horse-assisted therapy on socio-emotional behaviors in children with autism. Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medical Research. 2024;25(9):43-58. [DOI:10.9734/jocamr/2024/v25i9570]

30. Gabriels RL, Agnew JA, Holt KD, Shoffner A, Zhaoxing P, Ruzzano S, et al. Pilot study measuring the effects of therapeutic horseback riding on school-age children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012;6(2):578-88. [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.007]

31. Staples KL, Reid G. Fundamental movement skills and autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40(2):209-17. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-009-0854-9] [PMID]

32. Dziuk M, Larson JG, Apostu A, Mahone EM, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH. Dyspraxia in autism: association with motor, social, and communicative deficits. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49(10):734-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00734.x] [PMID]

33. Bodison SC. Developmental dyspraxia and the play skills of children with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015;69(5):1-6. [DOI:10.5014/ajot.2015.017954] [PMID]

34. Venetsanou F, Kambas A, Aggeloussis N, Serbezis V, Taxildaris K. Use of the Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency for identifying children with motor impairment. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49(11):846-8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00846.x] [PMID]

35. Qeysari SF, Sheikh M, Homanian D, Bagherzadeh F. Comparing the effects of play-based training and therapeutic horseback riding on the Stanford social dimensions in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: examining the theory of social motivation. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2025;14(1):40-55. [DOI:10.32598/SJRM.14.1.3279]

36. Peters BC, Wood W, Hepburn S, Moody EJ. Preliminary efficacy of occupational therapy in an equine environment for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2021;52(9):4114-28. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-021-05278-0] [PMID]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |