Volume 12, Issue 2 (9-2026)

J Sport Biomech 2026, 12(2): 210-222 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Farjad Pezeshk A, Sadeghi H, Mousavi Z, Bijari M. Effects of Sports Surface Stiffness on Time–Frequency Features of Vertical Ground Reaction Forces During Hopping. J Sport Biomech 2026; 12 (2) :210-222

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-475-en.html

URL: http://biomechanics.iauh.ac.ir/article-1-475-en.html

1- Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Department of Sport Sciences, University of Birjand, Birjand, Iran.

2- Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Department of Sport Biomechanics, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Department of Sport Biomechanics, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1778 kb]

(84 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (271 Views)

Full-Text: (42 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

The design of sports environments requires careful integration of ergonomic principles to enhance safety, performance, and athlete well-being. Among the mechanical properties of sports surfaces, stiffness is particularly influential, as it shapes the biomechanical responses of the lower limbs during dynamic activities. Previous studies have documented athletes’ adaptive strategies in modulating leg stiffness in response to surface compliance, which affects energy transfer, neuromuscular control, and injury risk (1–4). However, inconsistencies remain in the literature regarding the influence of stiffness values typical of commercial sports flooring (200–500 kN/m), which may be insufficient to induce substantial biomechanical changes (9,12). Experimental studies using much softer surfaces (<100 kN/m) have shown pronounced alterations in leg stiffness and energy dynamics, but the ecological relevance of these findings for real-world sports settings is limited. To address these gaps, the present study investigated how variations in surface stiffness within the common indoor range (300–500 kN/m) affect lower-limb mechanical responses. Specifically, the study examined whether stiffness changes within this practical range produce measurable differences in ground reaction force (GRF) characteristics during hopping. Emphasis was placed on frequency-domain features of the vertical GRF, given their emerging relevance in identifying loading patterns associated with performance demands and injury mechanisms. The overarching goal was to generate evidence-based ergonomic recommendations for the design of sports surfaces that optimize both safety and functional performance in recreational and competitive environments.

2. Methods

A repeated-measures experimental design was used to evaluate the effects of surface stiffness on vertical ground reaction forces during hopping. Prior to data collection, statistical power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1 to determine the required sample size for repeated-measures ANOVA. Assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), α = 0.05, and statistical power of 0.80, a sample of 30 participants was deemed adequate, yielding an actual power of 0.82. Thirty male physical education students aged 20–30 years, each with at least five years of regular training experience, were recruited through purposive sampling. Inclusion criteria required participation in a minimum of three training sessions per week to ensure consistent physical conditioning. Exclusion criteria included recent musculoskeletal injury, neurological disorders, or unwillingness to complete the protocol. The experimental surface consisted of a two-layer structure: a 5-mm wooden parquet top layer (50 × 50 cm) mounted on a 20-mm compressed wood base. To simulate resilient sports flooring, four to six steel springs (50 and 100 kN/m stiffness, constructed from 17-7 A313 steel) were installed at the corners, enabling adjustable stiffness configurations. The platform allowed vertical displacement via linear bearings, permitting controlled manipulation of surface stiffness. Four stiffness conditions were tested: 300, 400, and 500 kN/m, along with a rigid force plate serving as the baseline condition.

Vertical ground reaction forces (vGRF) were recorded using an AMTI force plate embedded at the center of the surface. Environmental conditions—including temperature, surface texture (aside from spring configuration), and time of day—were standardized across all trials. Hopping frequency was controlled at 2.2 Hz using a digital metronome, corresponding to participants’ preferred hopping frequency (2). Trials were accepted only when execution frequency remained within ±2% of the target. Each participant performed 30 familiarization hops on each surface, followed by 15 test hops per condition, with three-minute rest intervals between conditions. Kinetic data were filtered using a fourth-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 50 Hz. Hops 6–10 from each trial were analyzed to minimize variability. Peak vGRF values were normalized to body mass. Frequency-domain analysis was performed using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) in MATLAB 16.0, from which median frequency (Fmedian) and the frequency containing 99.5% of total signal power (F99.5) were extracted (14). Statistical comparisons across stiffness conditions were conducted using repeated-measures ANOVA (α = 0.05). When significant main effects were identified, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were performed. All analyses were completed using SPSS version 25.0.

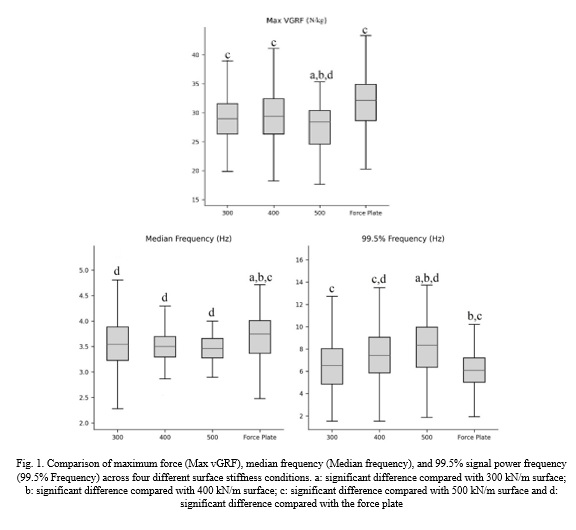

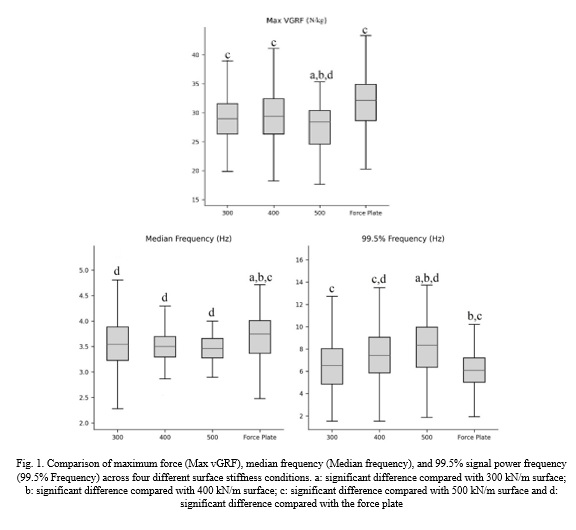

3. Results

The results presented in Figure 1 show that the force plate condition yielded the highest Fmedian (3.69 ± 0.44 Hz), which was significantly greater than all spring-based surfaces (p < 0.001). The 300, 400, and 500 kN/m surfaces produced lower Fmedian values (3.51 ± 0.50, 3.48 ± 0.37, and 3.45 ± 0.30 Hz, respectively). The highest F99.5 values were observed at 500 kN/m (8.23 ± 3.24 Hz), indicating a greater proportion of high-frequency content in the GRF signal. In contrast, the force plate produced the lowest F99.5 (5.86 ± 1.97 Hz). Normalized peak ground reaction forces were lowest on the 500 kN/m surface (27.92 ± 4.11 N/kg), significantly lower than those on the 300 kN/m (29.08 ± 4.44 N/kg), 400 kN/m (29.31 ± 5.06 N/kg), and force plate (31.88 ± 5.01 N/kg) conditions (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that the stiffest spring surface (500 kN/m) reduced peak loading while simultaneously increasing the frequency content of the GRF signal, reflecting sharper and more rapid force application. Conversely, the softest surface (300 kN/m) produced smoother, lower-frequency force patterns, which may suggest more controlled neuromechanical responses. Overall, the frequency-domain analysis demonstrated that surface stiffness meaningfully influences neuromechanical strategies during hopping. Harder surfaces elicited rapid, high-frequency loading, whereas softer surfaces promoted more distributed, lower-frequency force application. The intermediate stiffness condition (400 kN/m) appeared to balance these effects, producing moderate peak forces and frequency values.

1. Introduction

The design of sports environments requires careful integration of ergonomic principles to enhance safety, performance, and athlete well-being. Among the mechanical properties of sports surfaces, stiffness is particularly influential, as it shapes the biomechanical responses of the lower limbs during dynamic activities. Previous studies have documented athletes’ adaptive strategies in modulating leg stiffness in response to surface compliance, which affects energy transfer, neuromuscular control, and injury risk (1–4). However, inconsistencies remain in the literature regarding the influence of stiffness values typical of commercial sports flooring (200–500 kN/m), which may be insufficient to induce substantial biomechanical changes (9,12). Experimental studies using much softer surfaces (<100 kN/m) have shown pronounced alterations in leg stiffness and energy dynamics, but the ecological relevance of these findings for real-world sports settings is limited. To address these gaps, the present study investigated how variations in surface stiffness within the common indoor range (300–500 kN/m) affect lower-limb mechanical responses. Specifically, the study examined whether stiffness changes within this practical range produce measurable differences in ground reaction force (GRF) characteristics during hopping. Emphasis was placed on frequency-domain features of the vertical GRF, given their emerging relevance in identifying loading patterns associated with performance demands and injury mechanisms. The overarching goal was to generate evidence-based ergonomic recommendations for the design of sports surfaces that optimize both safety and functional performance in recreational and competitive environments.

2. Methods

A repeated-measures experimental design was used to evaluate the effects of surface stiffness on vertical ground reaction forces during hopping. Prior to data collection, statistical power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1 to determine the required sample size for repeated-measures ANOVA. Assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), α = 0.05, and statistical power of 0.80, a sample of 30 participants was deemed adequate, yielding an actual power of 0.82. Thirty male physical education students aged 20–30 years, each with at least five years of regular training experience, were recruited through purposive sampling. Inclusion criteria required participation in a minimum of three training sessions per week to ensure consistent physical conditioning. Exclusion criteria included recent musculoskeletal injury, neurological disorders, or unwillingness to complete the protocol. The experimental surface consisted of a two-layer structure: a 5-mm wooden parquet top layer (50 × 50 cm) mounted on a 20-mm compressed wood base. To simulate resilient sports flooring, four to six steel springs (50 and 100 kN/m stiffness, constructed from 17-7 A313 steel) were installed at the corners, enabling adjustable stiffness configurations. The platform allowed vertical displacement via linear bearings, permitting controlled manipulation of surface stiffness. Four stiffness conditions were tested: 300, 400, and 500 kN/m, along with a rigid force plate serving as the baseline condition.

Vertical ground reaction forces (vGRF) were recorded using an AMTI force plate embedded at the center of the surface. Environmental conditions—including temperature, surface texture (aside from spring configuration), and time of day—were standardized across all trials. Hopping frequency was controlled at 2.2 Hz using a digital metronome, corresponding to participants’ preferred hopping frequency (2). Trials were accepted only when execution frequency remained within ±2% of the target. Each participant performed 30 familiarization hops on each surface, followed by 15 test hops per condition, with three-minute rest intervals between conditions. Kinetic data were filtered using a fourth-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 50 Hz. Hops 6–10 from each trial were analyzed to minimize variability. Peak vGRF values were normalized to body mass. Frequency-domain analysis was performed using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) in MATLAB 16.0, from which median frequency (Fmedian) and the frequency containing 99.5% of total signal power (F99.5) were extracted (14). Statistical comparisons across stiffness conditions were conducted using repeated-measures ANOVA (α = 0.05). When significant main effects were identified, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were performed. All analyses were completed using SPSS version 25.0.

3. Results

The results presented in Figure 1 show that the force plate condition yielded the highest Fmedian (3.69 ± 0.44 Hz), which was significantly greater than all spring-based surfaces (p < 0.001). The 300, 400, and 500 kN/m surfaces produced lower Fmedian values (3.51 ± 0.50, 3.48 ± 0.37, and 3.45 ± 0.30 Hz, respectively). The highest F99.5 values were observed at 500 kN/m (8.23 ± 3.24 Hz), indicating a greater proportion of high-frequency content in the GRF signal. In contrast, the force plate produced the lowest F99.5 (5.86 ± 1.97 Hz). Normalized peak ground reaction forces were lowest on the 500 kN/m surface (27.92 ± 4.11 N/kg), significantly lower than those on the 300 kN/m (29.08 ± 4.44 N/kg), 400 kN/m (29.31 ± 5.06 N/kg), and force plate (31.88 ± 5.01 N/kg) conditions (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that the stiffest spring surface (500 kN/m) reduced peak loading while simultaneously increasing the frequency content of the GRF signal, reflecting sharper and more rapid force application. Conversely, the softest surface (300 kN/m) produced smoother, lower-frequency force patterns, which may suggest more controlled neuromechanical responses. Overall, the frequency-domain analysis demonstrated that surface stiffness meaningfully influences neuromechanical strategies during hopping. Harder surfaces elicited rapid, high-frequency loading, whereas softer surfaces promoted more distributed, lower-frequency force application. The intermediate stiffness condition (400 kN/m) appeared to balance these effects, producing moderate peak forces and frequency values.

4. Discussion

This study provides new evidence on how sports surface stiffness within the practical indoor range of 300–500 kN/m influences lower-limb biomechanics during cyclic hopping. Although many earlier studies have shown that athletes actively modulate leg stiffness to maintain center-of-mass dynamics across different surface compliances (1–4), much of this work has focused on extreme stiffness conditions that are not representative of real sports environments. The present findings demonstrate that even moderate variations in surface stiffness can measurably affect both time- and frequency-domain characteristics of vertical ground reaction forces (vGRF). The force plate, representing the stiffest and least compliant condition, produced the highest median frequency, consistent with prior work showing that rigid surfaces generate rapid force application and minimal energy absorption (4). Conversely, the highest F99.5 values were observed on the 500 kN/m spring surface, indicating sharp, high-frequency loading components. High-frequency force signals have been linked to neuromuscular responses associated with impact attenuation and potential injury mechanisms (14,15). These findings suggest that although stiffer spring surfaces reduce peak vGRF, they also induce rapid oscillatory forces that may increase neuromuscular demand. In contrast, the softest surface (300 kN/m) produced smoother, lower-frequency force patterns, aligning with earlier evidence that more compliant surfaces distribute forces over longer time intervals and promote controlled neuromechanical responses (1–3,6). Interestingly, peak vGRF was lowest—not on the softest surface—but on the 500 kN/m condition. This supports the leg–surface interaction theory, which proposes that individuals adapt ankle and lower-limb mechanics to maintain overall system stiffness when surface stiffness increases (2–4,9). Such adaptations may act as protective strategies to mitigate high-impact loading despite the surface’s stiffness.

The intermediate stiffness (400 kN/m) generated moderate peak forces and frequency-domain values, suggesting a biomechanically balanced response. Similar findings have been reported in studies on running tracks, drop jumps, and artificial flooring, where mid-range stiffness offers optimal trade-offs between loading, shock absorption, and performance (9–13). Overall, these results highlight that both very stiff and relatively soft surfaces impose distinct mechanical demands, whereas surfaces within the mid-range of 300–500 kN/m may provide an ergonomic optimum. Future research should incorporate diverse populations, explore footwear–surface interactions, and examine long-term adaptations to better understand the cumulative effects of surface stiffness on performance and injury risk.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were fully observed throughout the study. The research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the University of Birjand through its internal research funding program.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation, and final approval of the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

This study provides new evidence on how sports surface stiffness within the practical indoor range of 300–500 kN/m influences lower-limb biomechanics during cyclic hopping. Although many earlier studies have shown that athletes actively modulate leg stiffness to maintain center-of-mass dynamics across different surface compliances (1–4), much of this work has focused on extreme stiffness conditions that are not representative of real sports environments. The present findings demonstrate that even moderate variations in surface stiffness can measurably affect both time- and frequency-domain characteristics of vertical ground reaction forces (vGRF). The force plate, representing the stiffest and least compliant condition, produced the highest median frequency, consistent with prior work showing that rigid surfaces generate rapid force application and minimal energy absorption (4). Conversely, the highest F99.5 values were observed on the 500 kN/m spring surface, indicating sharp, high-frequency loading components. High-frequency force signals have been linked to neuromuscular responses associated with impact attenuation and potential injury mechanisms (14,15). These findings suggest that although stiffer spring surfaces reduce peak vGRF, they also induce rapid oscillatory forces that may increase neuromuscular demand. In contrast, the softest surface (300 kN/m) produced smoother, lower-frequency force patterns, aligning with earlier evidence that more compliant surfaces distribute forces over longer time intervals and promote controlled neuromechanical responses (1–3,6). Interestingly, peak vGRF was lowest—not on the softest surface—but on the 500 kN/m condition. This supports the leg–surface interaction theory, which proposes that individuals adapt ankle and lower-limb mechanics to maintain overall system stiffness when surface stiffness increases (2–4,9). Such adaptations may act as protective strategies to mitigate high-impact loading despite the surface’s stiffness.

The intermediate stiffness (400 kN/m) generated moderate peak forces and frequency-domain values, suggesting a biomechanically balanced response. Similar findings have been reported in studies on running tracks, drop jumps, and artificial flooring, where mid-range stiffness offers optimal trade-offs between loading, shock absorption, and performance (9–13). Overall, these results highlight that both very stiff and relatively soft surfaces impose distinct mechanical demands, whereas surfaces within the mid-range of 300–500 kN/m may provide an ergonomic optimum. Future research should incorporate diverse populations, explore footwear–surface interactions, and examine long-term adaptations to better understand the cumulative effects of surface stiffness on performance and injury risk.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were fully observed throughout the study. The research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the University of Birjand through its internal research funding program.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation, and final approval of the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/11/29 | Accepted: 2025/12/11 | Published: 2025/12/12

Received: 2025/11/29 | Accepted: 2025/12/11 | Published: 2025/12/12

References

1. Stefanyshyn DJ, Nigg BM. Energy and performance aspects in sports surfaces. Sports Biomechanics. 2003;2(1):31-46.

2. McMahon TA, Greene PR. The influence of track compliance on running. Journal of Biomechanics. 1979;12(12):893-904. [DOI:10.1016/0021-9290(79)90057-5] [PMID]

3. Farley CT, Houdijk HH, Van Strien C, Louie M. Mechanism of leg stiffness adjustment for hopping on surfaces of different stiffnesses. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1998;85(3):1044-55. [DOI:10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.1044] [PMID]

4. Kerdok AE, Biewener AA, McMahon TA, Weyand PG, Herr HM. Energetics and mechanics of human running on surfaces of different stiffnesses. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;92(2):469-78. [DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01164.2000] [PMID]

5. Arampatzis A, Stafilidis S, Morey-Klapsing G, Brüggemann GP. Interaction of the human body and surfaces of different stiffness during drop jumps. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2004;36(3):451-9. [DOI:10.1249/01.MSS.0000117166.87736.0A] [PMID]

6. Birch JV, Kelly LA, Cresswell AG, Dixon SJ, Farris DJ. Neuromechanical adaptations of foot function to changes in surface stiffness during hopping. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2021;130(4):1196-204. [DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00401.2020] [PMID]

7. Moritz CT, Farley CT. Passive dynamics change leg mechanics for an unexpected surface during human hopping. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2004;97(4):1313-22. [DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00393.2004] [PMID]

8. Willwacher S, Fischer KM, Rohr E, Trudeau MB, Hamill J, Brüggemann GP. Surface stiffness and footwear affect the loading stimulus for lower extremity muscles when running. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2022;36(1):82-9. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003410] [PMID]

9. Stafilidis S, Arampatzis A. Track compliance does not affect sprinting performance. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2007;25(13):1479-90. [DOI:10.1080/02640410601150462] [PMID]

10. Wróblewska Z, Kowalczyk P, Przednowek K. Leg stiffness and energy minimisation in human running gaits. Sports Engineering. 2024;27(2):1-10. [DOI:10.1007/s12283-024-00462-8]

11. Ismail SI, Nunome H, Lysdal FG, Kersting UG, Tamura Y. Futsal playing surface characteristics significantly affect perceived traction and change of direction performance among experienced futsal players. Journal of Sports Biomechanics. 2022;11(1):1-12. [DOI:10.1080/14763141.2022.2143415] [PMID]

12. Maquirriain J. The interaction between the tennis court and the player: How does surface affect leg stiffness? Sports Biomechanics. 2013;12(1):48-53. [DOI:10.1080/14763141.2012.725088] [PMID]

13. Farjad Pezeshk A, Sadeghi H, Shariatzadeh M, Ilbeigi S. Shifting joint regulation: The influence of hard spring surfaces on lower limb mechanics during hopping. Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology. 2025;1(1):1-12. [DOI:10.1177/17543371251353664]

14. Piri E, Jafarnezhadgero A, Stålman A, Alihosseini S, Panahighaffarkandi Y. Comparison of the ground reaction force frequency spectrum during walking with and without anti-pronation insoles in individuals with pronated feet. Journal of Sports Biomechanics. 2025;11(1):20-33. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.11.1.20]

15. Wurdeman SR, Huisinga JM, Filipi M, Stergiou N. Multiple sclerosis affects the frequency content in the vertical ground reaction forces during walking. Clinical Biomechanics. 2011;26(2):207-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.09.021] [PMID]

16. Hobara H, Inoue K, Muraoka T, Omuro K, Sakamoto M, Kanosue K. Leg stiffness adjustment for a range of hopping frequencies in humans. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010;43(3):506-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.040]

17. Mohamadian MA, Sadeghi H, Khaleghi Tazji M. The relationship between lower extremity stiffness with selected biomechanical variables during vertical jumps in healthy active men. Journal of Sports Biomechanics. 2018;4(2):29-38.

18. Ashrostaghi M, Pezeshk AF, Sadeghi H, Shirzad E. Comparison of prediction ability between preferred, controlled, and maximal hopping. Series on Biomechanics. 2022;37(1):1-12. [DOI:10.7546/SB.36.2022.02.11]

19. Pezeshk AF, Yousefi M, Ilbeigi S, Shanbehzadeh S. The assessment of primary joint in 2.2 Hz hopping using factor analysis. Series on Biomechanics. 2023;37(2):1-12. [DOI:10.7546/SB.09.04.2023]

20. Farjad Pezeshk SA, Sadeghi H, Shariatzadeh M, Safaie Pour Z. Effect of surface stiffness on the risk factors related to ground reaction force during two-leg landing. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020;9(2):318-25.

21. Farjad Pezeshk A, Sadeghi H, Safaeepour Z, Shariat Zadeh M. The effect of a custom area elastic surface with different stiffness on hopping performance and safety with an emphasis on familiarity to the surface. Journal of Advanced Sport Technology. 2017;1(1):5-14.

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |